Month: June 2012

A lot depends on your priorities

I did a quick writeup of Senator McCain’s appearance yesterday at the Middle East Institute Turkey Conference, which is posted on their website this morning (thank a spam filter for the delay):

Senator John McCain was uncharacteristically subdued in a key note address yesterday to the Middle East Institute/Institute of Turkish Studies conference on Turkey. He prodded President Obama to be more outspoken in denouncing the Assad regime and advocated a “safe zone” inside Syria along the Turkish border, but only in response to a question. He discounted the likelihood of NATO action, which the Europeans oppose, and suggested that the U.S. and Turkey should form the core of a coalition of the willing to support the Syrian opposition with arms and training.

The Senator opened with a denunciation of the Syrian downing of a Turkish jet, calling it an unnecessary and unacceptable act of aggression. But then he turned quickly to focus on Turkey’s positive evolution into a more inclusive and representative democracy experiencing strong economic growth. He also noted troubling developments: Turkey’s jailing of journalists, its prosecutions of army officers and the deterioration of its relations with Israel.

The U.S., McCain said, should give wholehearted military and intelligence support to Turkey in its fight against Kurdish terrorists (the PKK). But the bilateral relationship should broaden its focus to free trade, military modernization, missile defense and strategic cooperation in Afghanistan, the Arab Spring and other contexts where democracy, human rights and rule of law are at stake. Turkey, he said, sets a standard for democracy in Muslim countries and is an attractive example to many throughout the Muslim world.

McCain appealed for stronger U.S. leadership in speaking up for the people of Syria and countering Russian and Iranian support to the Assad regime, which includes both arms and personnel. A “safe zone” on the Turkish/Syrian border would provide the fragmented and unreliable opposition with a place where it could coalesce. This would require intervention from the air (as in Bosnia and Kosovo) but not, he thought, boots on the ground (forgetting of course that on the “day after” U.S. troops were needed in both Bosnia and Kosovo). Asked about the Annan peace plan that provides for a peaceful transition, McCain reacted with disdain, saying that Bashar al Assad would have to be forced out.

The current situation, McCain emphasized, is not acceptable. Sectarian violence is on the increase, as is exploitation of the situation by extremists. It will only get worse if the U.S. fails to lead. It is not even leading from behind at this point. It is not enough for the White House to say that Bashar al Assad’s fall is inevitable. We have to make it happen.

McCain acknowledged American war weariness but underlined the moral imperative to speak out and to act. Absent from his remarks was consideration of the impact of American and Turkish air attacks to create a “safe zone” on Russian support for the P5+1 negotiations with Iranian on its nuclear program and on the Northern Distribution Network that supplies NATO troops in Afghanistan. Those who think Afghanistan and Iran should have priority in American foreign policy won’t go along with the Senator, almost no matter what Bashar al Assad does to his own people. A lot of what people think should be done in Syria depends on what your priorities are.

No laughing matter

Ilona Gerbakher reports:

Monday, as Egypt’s elections results were being broadcast to the world, Freedom House and the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies met to discuss “Revolution under siege: is there hope for Egypt’s democratic transition?” Two of the speakers were unable to say the phrase “President Morsi” with a straight face, which is perhaps a good indicator of the future of his presidency.

Anwar Sadat, Chairman of Egypt’s Reform and Development Party, believes that it doesn’t matter who is president of Egypt, but the fact that the election took place at all proves that there is hope for a democratic transition. He urges America not to worry about the Muslim Brotherhood or further unrest in Egypt: now that a president for “all Egyptians” has been declared, he believes things in Egypt will settle down. Egyptians need to look forward, not backwards–they must reconcile themselves to a united future and continue the democratic transition.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) will inevitably hand over power. But even in this united, newly democratic Egypt, old economic and political challenges will prevail, particularly the Sudanese border, Libya and the “traditional” Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He warned the revolution will not bring magic. Without unity in the post-revolutionary period there will be no security, no stability and no safety.

Mohammed Elmenshawy, Director of the Languages and Regional Studies Program at the Middle East Institute, disagreed with the idea that the identity of the president does not matter: if Egypt had elected Ahmed Shafiq, torch-bearer of the ancien regime, it would have marked the end of the revolution. We are in a symbolic moment: the election of a man outside of the elite circle who have ruled Egypt for the last 60 years. He is also the first freely elected head of an Arab State. Morsi is truly a man of the people. He is a typical middle class Egyptian. His wife looks and dresses like an ordinary Egyptian woman. The fact that he is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood is also very important: they are the only organized people on the street. Neither the liberal/secularist Egyptians nor the military elite are “on the streets, getting their hands dirty” as effectively and consistently as the Muslim Brotherhood.

Elmenshawy cautions, however, that the majority of Egyptians did not vote for President Morsi, but rather against his opposition. Morsi does not have the solid majority political mandate that he needs in order to effectively counter the SCAF and the Egyptian “deep state.” The strong man presidency so typical of the Mubarak era is a thing of the past. Morsi will be hampered by a weakened executive role in an Egypt that is more polarized than ever before. What is the role of the United States in this new post-revolutionary Egypt? “You had better stay out, you better shut up.”

Nancy Okail, Director of Freedom House Egypt and recent guest of the Egyptian penitentiary system, asks whether this election is truly a new situation for Egypt, or merely a perpetuation of the past? She agrees with Elmenshawy’s assertion that the vote was not for Morsi but against Shafiq and the SCAF. She notes that over the sixteen months since Mubarak was forced out of office, SCAF has taken several steps to significantly curtail the power of the executive branch: it decreed that military intelligence can search and arrest civilians without due process, dissolved parliament and limited the power of the constituent assembly. An article in the new constitution gives veto power over the constitution to SCAF, allowing it to cancel any part of the constitution they see as “inappropriate.”

All of these actions limit the power of the incoming president and shore up SCAF’s power. In addition, SCAF is playing up to wide-spread populist and xenophobic sentiment in Egypt, branding Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood as pro-American, splintering Morsi’s already fragile majority. The message from SCAF to Morsi is that he is not going to be sitting on a very stable seat.

In what was perhaps a symbolic moment, she asked, “How will President Morsi…,” stopped herself mid-phrase, and told the audience “I’m trying to get used to it.” She laughed, and the audience chuckled with her. Elmenshawy in a subsequent discussion was also unable to say the phrase “President Morsi” without chuckling to himself, laughter rippling through his audience.

But the weakness of newly-elected President Morsi is no laughing matter. Will Morsi be the person to bring Egypt together? Sadat’s optimism aside, the laughter in the audience suggests not.

A smooth landing after so much turbulence?

Travel has made me late to post on the election of Mohammed Morsi as Egypt’s president, so it is unlikely I’ll say anything you haven’t heard before. But maybe it will be useful if I explain why some like me who advocated a vote for Ahmed Shafiq is happy to see the election of Morsi.

I suggested voting for Shafiq when it looked as if the election of Morsi might give the Muslim Brotherhood a monopoly on institutional power in Egypt, as it already controlled the parliament. Shortly thereafter, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) used a Supreme Constitutional Court decision to close the parliament and arrogate legislative power to itself. So Morsi’s election is breaking the army’s monopoly on power, rather than Shafiq breaking the Brotherhood’s monopoly on power. The point is the same: Egypt is a deeply divided society getting ready to write a constitution. The broadest possible representation in power is what the country needs.

It would be hard to resist the joy some Egyptians are expressing at the election of Morsi, who has gone out of his way to reach out to the broadest possible spectrum of Egyptian society. He has even resigned from the Brotherhood and praised the army, underlining his intention to be the president of all Egyptians. Some will gripe that he can leave the Brotherhood but the Brotherhood doesn’t leave him. Others will doubt his sincerity in promising to treat women and Christians equally. Still others will worry that his promise to uphold international agreements won’t apply to the peace treaty with Israel, on which the Brotherhood has in the past advocated a referendum. There are enormous uncertainties surrounding Morsi.

The greatest of these is what powers he will actually exercise. Even former president Hosni Mubarak kept a parliament, which is nice to have around when you need legislation on controversial matters of no import to the army. Who would want to decide on the level of food subsidies in Egypt today? Or pension payments? Or female genital mutilation? Not the army for sure. It should be content to keep control of its own budget and economic enterprises while blocking any moves towards accountability for crimes committed under the Mubarak regime. I don’t think it will be long before we see the army unhappy with its legislative responsibilities, but it will be difficult to get rid of them. There is a strong likelihood that new legislative elections will bring another strong showing by the Islamist parties (the Brotherhood controlled 48 per cent of the seats after the last elections and the Salafists another quarter or so).

Meanwhile Morsi, has to put together a government, uncertain of its powers but confident of his own democratic legitimacy. It is not even clear where and how he will be sworn in, though I trust they’ll figure that one out. The SCAF will be overseeing the cabinet-formation process, and perhaps even vetoing particular names. One of Morsi’s lieutenants is saying

It will be a coalition government without an FJP [Freedom and Justice Party, the Muslim Brotherhood’s political party] majority and led by an independent figure.

That sounds smart to me. An Egyptian administrative court today threw out the arrest and detention powers that the army gave itself just a few days ago. If Morsi is patient and diligent, he may well find power on many issues gravitating in his direction, with the army content to protect its more immediate interests.

If that happens, I’ll be wondering again where the counterbalancing forces can be found. But Egypt has already been through a lot of turbulence. Dare I hope that, like my flight from Vienna today, things smooth out for a good landing?

Towards reconciliation

Here I am still at the OSCE’s Security Days, which in its third session is turning towards the question of reconciliation, “addressing the protracted conflicts and revitalizing dialogue.”

Janez Lenarčič, Director of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions (ODIHR) opens suggesting that it is obvious OSCE needs to move in this direction, since anything else raises risks of reigniting conflicts.

Erwan Fouéré, Special Representative of the OSCE Chairperson-in-Office for the Transdniestrian Settlement Process:

- We need to devote more attention to learning from other experiences. South Africa offers many lessons about the need to negotiate with your enemies and the role of women. The Northern Ireland process illustrates the need for patience and partnerhsip.

- The vital ingredient for success is trust between the sides. This is only achieved through dialogue. This is the prerequisite for taking risk and compromising.

- Peace implementation is as important as peace negotiation. Irreversibility should not be taken for granted. Much work still needed in Northern Ireland and Macedonia.

- A peace process requires reconciliation. It is difficult to build this into the settlement. South Africa is a good example. Northern Ireland still has a long way to go. Reconciliation cannot be imposed but needs to come from the region: Rekom, for example, in former Yugoslavia.

- It is vital to involve civil society. The earlier civil society is involved, the more likely a peace process will result in reconciliation.

Kai Eide, former UN Special Representative for Afghanistan and Head of the UN Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), underlines the gap between the deep level of engagement in Afghanistan and the little understanding of the situation. Confidence building measures (CBMs) have not yet convinced the parties that talk is better than fight. We need to look at time-limited, space-limited ceasefires. OSCE has the kind of experience with CBMs that is needed in Afghanistan. The conflict has deepened fissures in Afghan society–internationals need to pay attention to this. There are too many actors trying to get a negotiation process started. The internationals should not try to impose a solution. The Afghans need to deal with each other on issues like decentralization and division. Eventually there will have to be reintegration of former fighters. That requires confidence in the settlement. Does the OSCE have relevant experience? There are two other issues: political reform and accountability for past behavior. Does the OSCE have experience in these areas? Even within its own area, does the OSCE complete the job?

Aleksandr Nikitin, Director for Euro-atlantic Security at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, notes the relatively small financial and manpower contributions of Russia to UN peacekeeping operations, which is inconsistent with Putin’s global power ambitions. The Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CTSO) is one of the answers. It is the West that expanded the UN mandate in Libya to regime change.

CTSO can provide interoperable and jointly trained forces. This follows the precedent of the EU Combined Joint Task Forces. Russia has contributed to a number of peacekeeping operations in Bosnia, Kosovo, Moldova, Abkhazia, Ossetia, Tajikistan, and elsewhere. CIS has delegated authority in some of these operations; impartiality has not been observed at all stages. Peace enforcement has sometimes been involved.

NATO-Russia Council mechanism has not worked well. The international community needs crisi response forces. NATO has 20,000. The EU has 1500. CSTO has 15,000, plus another 1500 peacekeepers. NATO and CSTO forces should exercise together and develop interoperability. There is a need for a coordination council of international organizations: NATO, CSTO and OSCE.

Jonathan Sisson, a former adviser to the Swiss Foreign Ministry for the Balkans and Caucusus, underlines the importance of the human rights legacy of protracted armed conflict. Most victims suffer long term health and social welfare impacts, they live in close proximity to perpetrators, the state is often corrupt and weak, there are parallel power structures with links to organized crime, a culture of violence and militarism prevails. Realizing the rights of victims and ensuring accountability are vital pieces of reconciliation.

Dealing with the past is a prerequisite for reconcilation. The guiding principles (“Joinet/Orentlicher”) are

- The right to know

- The right to justice

- The right to reparations

- Guarantees of non-reccurrence

Reconciliation is a process of conflict transformation. Dialogue should focus on acknowledging and addressing past absues, developing a shared vision, building a new basis for social identity, transforming oppressive structures and ideologies, and creating conditions for behavioral and attitudinal change.

There is a need to focus on the paradoxes of reconciliation:

- recognition of pain and articulation of a common future;

- concerns for exposing what happened and for letting go in favor of a renewed relationship;

- redressing wrongs balanced against the need for stability of the status quo;

- the burden of reconciliation is placed on the shoulders of victims.

The Turkish ambassador appeals for more attention to conflict resolution, which requires political will. The OSCE can help to trigger political will by creating long-term perspectives for the countries of the region. Regional actors need to initiate the reconciliation process. OSCE can contribute in Afghanistan, but Afghanistan cannot be OSCE’s raison d’être.

A Georgian expert wonders whether there is really a need for reconciliation. The local people don’t feel much need for it. The conflict had little to do with their needs. Settlement is required before reconciliation. The Armenian representative suggests briefings on conflict resolution and reconciliation in cases not under OSCE auspices. It is important to understand that human rights, especially non-discrimination and freedom of expression, are a prerequisite to reconciliation. Which reparations, collective or individual, are most effective?

The chair offers a Twitter/Facebook question: is reconciliation a grass roots affair, or is it between states? The Croatian ambassador doubts whether the new generation of leaders will be interested in reconciliation in former Yugoslavia. A Greek representative asks about what instruments the OSCE can offer by way of mediation support.

Sisson underlines the difference between post-conflict reconciliation and reconciliation attempted before a conflict settlement. But there are things that can be addressed before settlement: documentation and missing persons, for example. Reparations should be on the table from the first, even if it is not decided until after settlement. Witness protection is a vital component of ensuring the right to know, which also involves access to information in the state’s files. Collective reparations can be problematic because victims may not accept them as as a benefit. Both top-down and bottom-up efforts are needed.

Nikitin suggests international organizations may be satisfied with freezing conflict. Reconciliation is not always or immediately necessary. There may be a postponed solution. In Afghanistan half the population is under 15, so methods for reconciliation may have to be different. There is no need for reconciliation yet between Russia and Georgia. Reconciliation is a broader issue than between warring parties: we are still doing it for the Cold War.

Kai Eide notes that reconciliation is hard in a situation like Kosovo where there were no institutions at the end of the war. Likewise in Afghanistan, where there are no functioning legal institutions. This cements a situation that makes it hard to undertake reconciliation, which is necessarily both top-down and bottom-up. Facilitation is a better concept than mediation.

Fouéré underlines that reconciliation efforts are difficult and may have only limited impacts, but they are still necessary. In the Balkans there is an enormous amount of work still to be done, but the effort has to come from the region.

Lenarcic in closing underlines the importance of trust, ownership and inclusiveness (women and civil society) as prerequisites for reconciliation. Truth, justice and forgiveness (not revenge) are essential to successful reconciliation. If the international community wants to contribute it needs to be knowledgeable and have the confidence of the parties to the conflict.

I am not going to post on the fourth session, which is when I will present. My contribution has been posted below.

Reconciliation: a new vision for OSCE?

I am speaking at the OSCE “Security Days” today in Vienna on a panel devoted to this topic. Here is what I plan to say, more or less:

Reconciliation is hard. Do I want to be reconciled to someone who has done me harm? I may want an apology, compensation, an eye for an eye, but why would I want to be reconciled to something I regard as wrong, harmful, and even evil?

At the personal level, I may be able to escape the need for reconciliation. I can harbor continuing resentment, emigrate, join a veterans’ organization and continue to dislike my enemy. I can hope that my enemy is prosecuted for his crimes and is sent away for a long time. I don’t really have to accept his behavior. Many don’t.

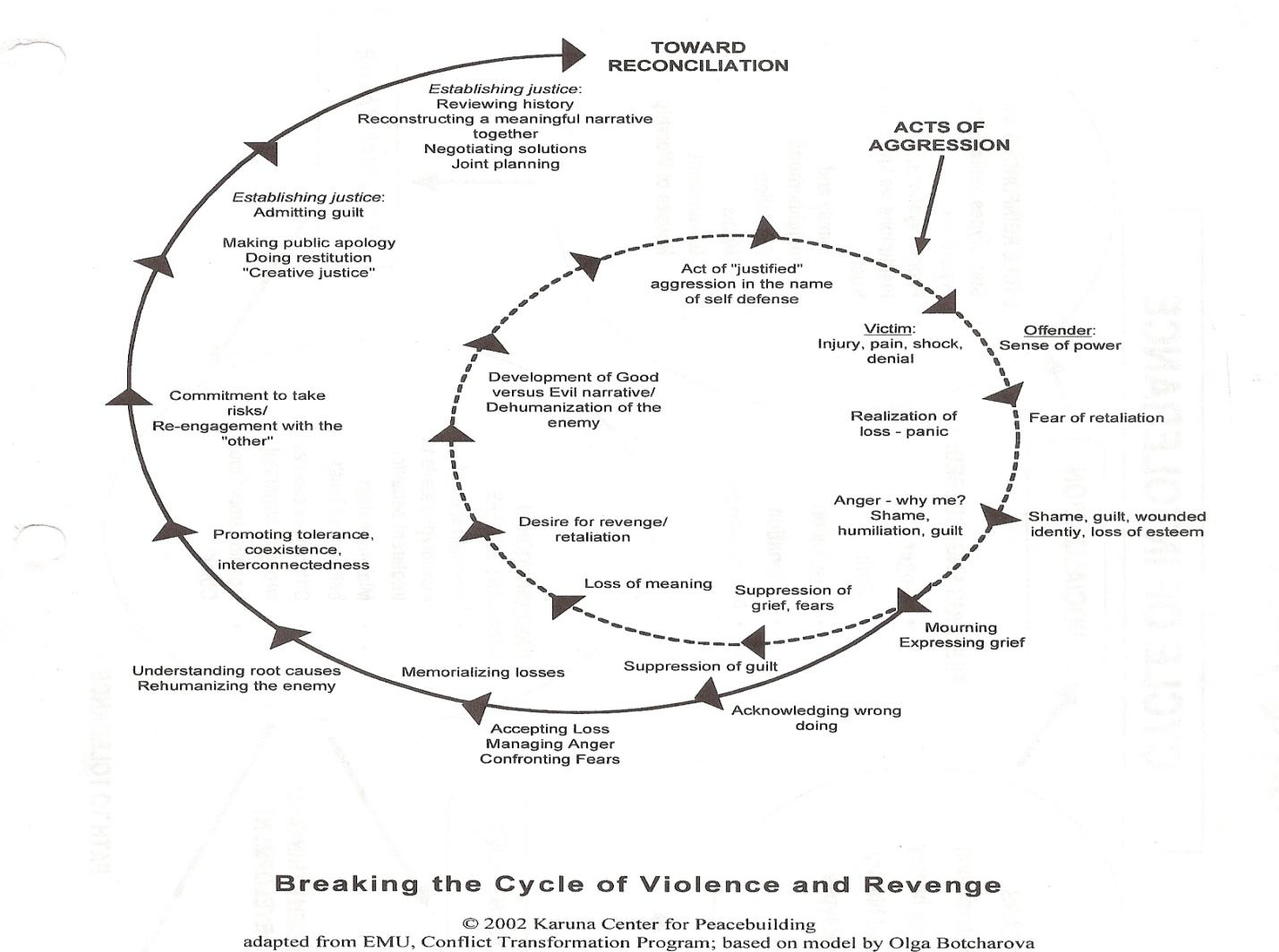

But at the societal level lack of reconciliation has consequences. It is a formula for more violence. We remain trapped in the inner circle of this classic diagram, in a cycle of violence. Victims, feeling loss and desire for revenge, end up attacking those they believe to be perpetrators, who eventually react with violence:

What takes us out of the cycle of violence and retaliation? The critical step is acknowledging wrong doing, a step full of risk for perpetrators and meaning for victims. But once wrong doing is acknowledged, victims can begin to accept loss, manage anger and confront fears. This initiates a virtuous cycle of mutual understanding, re-engagement, admission of guilt, steps toward justice and writing a common history.

What has all this got to do with OSCE? Some OSCE countries are still stuck in the inner cycle of violence, despite dialogue focused on practical confidence-building measures that moves the parties closer. But the vital step of acknowledging wrong has either been skipped entirely or given short shrift. Conflict management is a core OSCE function. The job will not be complete until OSCE re-discovers its role in reconciliation.

I know the Balkans best. We aren’t past the step of acknowledging wrongdoing in Bosnia and Kosovo. Even Greece and Macedonia are trapped in a cycle that could become violent. The situation is less than fully reconciled in Turkey, the Caucasus, Moldova and I imagine other places I know less well. Is there a good example of Balkans reconciliation? The best I know is Montenegro’s apology to Croatia for shelling Dubrovnik. That allowed them to build the positive relationship they have today.

Should reconciliation be a new OSCE vision? Its leadership and member states will decide, but here are questions I would ask if I were considering the proposition:

- How pervasive is the need for reconciliation in the OSCE?

- Would it make a real difference if reconciliation could be established as a norm?

- If it did become a new norm, how would we know when it is achieved?

- What would we do differently from what we do today?

I was in Kosovo earlier this month. There is little sign there of reconciliation: it is difficult for Belgrade and Pristina to talk with each other, they have reached agreements under pressure that are largely unimplemented, OSCE and other international organizations maintain operations there because of the risk of violence. There is little acknowledgement of wrong doing. The memorials are all one-sided: I drove past many well-marked KLA graveyards. We have definitely not reached the outer circle yet.

Would it make a difference if there were acknowledgement of wrong doing? Yes, it would. It would have to be mutual, since a good deal of harm has been done on both sides, even if the magnitude of the harm differs. Self-sustaining security in Kosovo will not be possible until that step has been taken. I would say the same thing about Bosnia, Kyrgystan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey and Armenia. Your North African partners might benefit from focus on reconciliation.

Dialogue is good. Reconciliation is better. Maybe OSCE should take the next difficult but logical step.

More shaping a security community

In a second session at the OSCE Security Days devoted to “Shaping a Security Community,” moderator Adam Kobieracki, Director of the OSCE Conflict Prevention Centre, opens with the comment that OSCE is not in crisis but needs to adapt to the new security environment and establish or develop appropriate security institutions.

Steven Pifer, Director of the Brookings Arms Control Initiative and Senior Advisor at CSIS, notes the absence of Russia from the treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE). Has the treaty in fact served its purposes? Is there any need for new limits? The real issue is subregions within the OSCE. It might be best to develop a general set of rules for subregions. Do you want limits on forces or transparency and confidence building measures? If there are to be limits, what should they be on? Tanks are far less important than the past. Unmanned aerial vehicles and surface to surface missiles are much important. So too are offensive capabilities. How do you deal with forces on the territory of states that do not want them there? This is not really an arms control issue. It is going to be hard to get traction on conventional arms control with political leaders in the OSCE area.

Adam Rotfeld, Co-chair of the Polish-Russian Working Group on Difficult Matters of the Polish Institute of International Affairs, notes that Europe has rarely been so free of threats, but there are still problems of trust and confidence. Fiscal problems are the big ones. Security issues are now not between states but within. OSCE initially helped to stabilize existing states. Then in the 1980s it managed to play a strong role in reducing armaments. Then it focused on conflict management. What is the new stage? What is needed is mutually assured stability.

General Vincenzo Comporini of the Italian Institute for International Affairs underlines growing global complexity. Growing populations, better health care, improved education and political awareness are challenging regimes that had appeared stable. Cheap availability of weapons is a complicating factor. First step should be analysis, including a clearinghouse for open intelligence. This intelligence should be shared in open dialogue with the states that are under challenge. This may appear utopian, but no more so than earlier OSCE goals.

Daniel Mockli, head of strategic trends analysis at the Center for Security Studies, notes fatigue with military intervention and looks forward to softer approaches. OSCE should focus on what it can really do. A security community may be too difficult. But there is a need for adaptation and for cooperative security efforts. OSCE should be about managing diversity, reassurance, engagement. There is a culture of dialogue, transparency and mutual learning that should guide the OSCE. Conventional arms control has crumbled. The political climate has deteriorated, threats have shifted to non-European sources, protracted conflicts have damaged the arms control regime. The goal should not be a new legal framework but rather a more political approach. Can we come up with a status neutral regime? No new regime will emerge overnight. Both limitations and transparency will be needed. We may be too confident about living in stability. There is still a need for predictability and mutual trust, which is what the OSCE should be about. The way forward is to manage protracted conflicts in a way that reduces their impact within the OSCE.

The Turkish ambassador underlines that security is indivisible. The protracted conflicts should not be separated out. Limitations, transparency and information exchange, as in the original CFE treaty, should continue to go together in future arrangements. The heart of the matter is deficit of confidence and trust. That is what we need to boost, so as to ensure predictability.

A Russian participant notes the need for impetus to generate political will. The negotiation process itself is an important part of the picture. The ongoing dialogue is itself valuable. We need to return to a culture of political-military dialogue. The Dutch ambassador suggests any OSCE member who wants be involved in new talks on conventional arms control. Focus should be on confidence-building. Protracted conflicts play an important role; we need to find a formula to handle them.

Mockli suggests the problem is not political will but political fragmentation. It is important to start a process even if the outcome is uncertain. OSCE has a unique toolbox for democratization issues that should be applied to the Arab awakening, but also inside the OSCE region. Camporini underlines that security is a real issue in the Mediterranean because of the Arab awakening. Syria is increasing tensions within the OSCE, which needs to pay attention to that crisis and offer itself as a model.

Rotfeld suggests OSCE is vulnerable because of renewed geopolitical bipolarity. But it is values that are important in the Arab awakening. Nongovernmental institutions are playing a key role today, especially in confronting unconventional risks. Government institutions are less relevant. The OSCE area is heterogeneous; security is not the same throughout. It is divisible and we need to be prepared to recognize that. Flexibility is key. There is no single recipe for building confidence. Pifer reiterates need for focus on subregions and need for first focus to be on confidence-building measures and transparency. Missile defense is a strategic offensive balance issue, but it won’t be decisive for ten years or more. He questions whether the Russian justification of its nuclear forces on the basis of the conventional imbalance is really sensible.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts