Month: December 2024

What the US should do in Syria

I found the above MEI event informative, especially Wael al Zayat’s proposals for shifting American policy. Starting about 39:30, he proposes:

- A general license for export of some priority goods and services to Syria, including in the finance and energy sectors. He says such licenses were issued for six months of earthquake relief in 2023.

- Humanitarian assistance for the Syrian people.

- Support to Syrian organizations concerned with transitional justice.

- Encouragement to the UN to return to Damascus for humanitarian, development, and political purposes.

These seem to me good ideas, if somewhat scattershot in presentation. Charles Lister goes on to note that the US is trying to engage. But he says delisting HTS as a terrorist organization will not happen quickly. It will be strictly conditional on HTS behavior.

US conditions

Secretary of State Blinken has outlined the conditions:

The United States reaffirms its full support for a Syrian-led and Syrian-owned political transition. This transition process should lead to credible, inclusive, and non-sectarian governance that meets international standards of transparency and accountability, consistent with the principles of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254.

The transition process and new government must also uphold clear commitments to fully respect the rights of minorities, facilitate the flow of humanitarian assistance to all in need, prevent Syria from being used as a base for terrorism or posing a threat to its neighbors, and ensure that any chemical or biological weapons stockpiles are secured and safely destroyed.

All this sounds reasonable, though it omits explicit insistence on pluralism. That will be a major issue, as HTS is an authoritarian organization that won’t readily tolerate political competition. While making friendly noises, it has already appointed a less than inclusive interim government to serve until March 1.

The Kurds, the Turks, and the Americans

Syria’s Kurds pose a knotty problem for the United States. The Americans have relied on Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the fight against the Islamic State. The Kurds involved are affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). Both the US and Turkey have designated the PKK as a terrorist group.

Turkey wants the PKK at least 30 km from its border and east of the Euphrates. Turkish-supported forces called the Syrian National Army are pushing the SDF in those directions now. The Kurds have lost their last stronghold west of the Euphrates (at Minbij). They fear that the Turkish-supported forces are aiming for Kobani. The Kurds made a bloody and successful stand at Kobani against the Islamic state in 2014 and 2015.

Meanwhile, HTS and the Kurds are making nice. HTS has sent conciliatory messages and the Kurds have agreed to use the Syrian opposition flag on territory they control. But HTS is heavily dependent on Turkish good will. The Americans are less than reliable backers. They have used the Kurdish alliance against IS but don’t want to clash with NATO ally Turkey. The outcome of this menage a trois is not yet clear. Time is fleeting, as future President Trump has said he wants Syria left to the Syrians. If he means it, the Kurds will then be to the mercy of the Turks. That won’t be a good place to be.

Breaking the Iran connection and working the Russia angle

The success of HTS in toppling the Assad regime was a big defeat for Russia and Iran. But Moscow is already negotiating with HTS to continue its air and naval bases in Latakia and Tartus, respectively. Iran is hoping the HTS success will be temporary. Tehran is no doubt doing all it can to make it so.

HTS will have little use for the Iranians and will not let want them back in Syria. They may have property and contracts that will need to be respected. But Damascus will no long welcome the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Lebanese Hezbollah, or the other Iranian proxy forces.

The Russia angle is more equivocal. HTS will want the Russian air force out but may want to keep the Russian navy in. That would strengthen its bargaining position with the West. The US and Europe will want the Russians completely out. They’ll need to ante up to make it happen. Delisting could be part of the price.

A lot of moving parts

Diplomacy is difficult even when there aren’t a lot of moving parts. Add the change of the American administration into the mix and it becomes worse than the Three Body Problem. But there are big opportunities in Syria to make a better life for Syrians. Not to mention to weaken Russia and Iran.

More remains to be done, but credit is due

Opposition and Turkish forces now control Syria’s northwest, northeast, north, south and the main cities of its north/south axis. But most of the west–the provinces of Latakia and Tartus–are still not fully in opposition control. Ditto much of the center.

The Alawites

The Alawite sect to which Bashar al Assad belonged constituted only about 10% of Syria’s population before the civil war. But Alawites are a plurality in the west. They live more in the countryside than in the main cities. The leader of the opposition, Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), has named a military commander for the west. He met with Alawite notables in Latakia Tuesday. @GregoryPWaters cites an Alawite professor present, who reports:

The broad, summarized headlines that we all felt were true:

– No to sectarianism absolutely

– No to violating the property of individuals and institutions

– No to division

– No going back, everyone was harmed by the previous regime in one way or another

That is as friendly a message from HTS as possible. It is not entirely surprising. HTS has been reaching out to Syria’s minorities to preserve Syria’s unity. The Alawites of Latakia and Tartus suffered a great under their co-religionist Assad. They lost a lot of young people in the war. They had to toe the line or risk the full weight of his repression. Many Sunnis and others resented their access to privilege and power.

The trick now is to somehow hold individuals who committed abuses accountable while not mistreatinthe rest. Many of Assad’s henchmen, Sunni as well as Alawite, will have fled to Latakia and Tartus. Ferreting them out and giving them fair trials will not be easy.

The Russians

Besides the Alawites, the Russians are a problem in the west. They operate the Syrian Khmeimim Air Base in Latakia and lease a naval base farther south in Tartus. The air base has since 2015 launched thousands of sorties against opposition forces and civilians. The naval base is Russia’s only naval facility in the Mediterranean. Turkey has closed the Bosporus to military traffic due to the war in Ukraine. So the Tartus base is particularly important to the Russians. The air base is not, as its role has been overtaken by events.

Still, Moscow is insisting on keeping both. Russia will be arguing that the Syrians shouldn’t rely too heavily on Turkey. HTS has not signaled that it wants them out. Putin will be lucky to retain the naval facility.

The Islamic State

Much of the white area on the above map is sparsely populated. But it hosts Islamic State cells. HTS will now have to shoulder the burden of eliminating them. It should be willing to do so, as the Islamic State is a rival, not an ally. But it isn’t easy. The Americans could be helpful from the air and might be willing. Someone should ask, or offer. Once HTS gets that done, the Americans will not want to stay in Syria. And future President Trump won’t want them to.

A remarkable job

HTS-led forces have done a remarkable job in a short time. The risks of fragmentation are still there, but lower than a week ago. Abu Mohammed al Jolani has sent the right political signals. There is still more to be done, but credit is due.

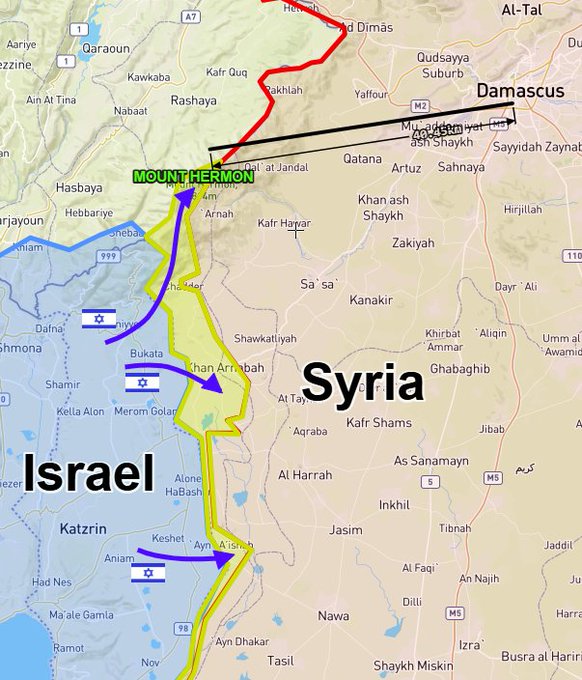

For now, Netanyahu is succeeding

Israel’s air force is destroying Syria’s navy, weapons manufacturing sites, chemical and other weapons depots. It is undertaking hundreds of sorties per day. The Israel Defense Force (IDF) has also seized control of the UN buffer zone on the Golan Heights. That was created in a 1974 agreement.

Location, location, location

None of this should be surprising. Syria for the moment can’t defend itself. Its longtime enemy is trying to weaken it further. Among many other advantages, Israel now occupies the peak of Mount Hermon. That has unimpeded electronic visibility over a good part of Syria, including the capital, and Lebanon. This is valuable real estate.

The Israelis can do this because the Syrian Arab Army has disintegrated and the Russians are not preventing it. While Assad was in power, Israel raided Syrian sites, but only with a wink and a nod from Moscow. Now it is unclear whether Moscow has no objection or is simply unwilling or unable to object. Syrian and Russian air defenses have not reacted to the Israeli attacks.

The American position

Former President Trump formally proclaimed in 2019 that the United States recognizes the Golan Heights as “part of Israel.” The Biden administration upheld that policy with a 2021 tweet. It is hard to picture Trump in a second term reversing it. He has signaled, not least with appointment of an evangelical Christian as ambassador, that he will back Israel. Even more than Biden did.

That does not necessarily mean the United States will want Israel to hold on to the UN buffer zone. But Netanyahu will no doubt press Trump hard on that issue. In the past, Trump has given the Israeli Prime Minister pretty much everything he has asked.

The new Syrian government has its hands full

Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS) has named Mohammed al Bashir as interim prime minister until March 1. He was the head of the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG). That is the government HTS empowered for several years in the territory it controlled in the northwest province of Idlib. Al Bashir and SSG officials have met with President Assad’s outgoing officials to arrange the transfer of responsibilities. This is far more orderly than one might have anticipated. Let’s hope it can continue that way. Syria’s economy and population need relief. Those are for now top priorities.

But no Syrian leader will fail eventually to claim all of the Golan Heights. Some HTS fighters have declared their next objective is Jerusalem. Their leader’s nom de guerre is Abu Mohammed al Jolani (more or less father of Mohammed of Golan). Least of all one whose parents came from there. Al Jolani’s father was an Arab nationalist and supporter of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Al Jolani himself says the second intifada radicalized him. Netanyahu will no doubt be hearing from him in due course.

But al Jolani has his hands full for the moment. Turkish-backed forces are attacking US-backed Kurdish forces in northern Syria. Al Jolani wants the Kurds to support the new regime. Turkiye President Erdogan, an important HTS backer, wants them pushed away from the Turkish border and east of the Eurphrates. That’s east of Manbij on the map below. The Turkish/Kurdish conflict could explode and weaken the unified effort HTS has tried to construct.

The broader picture

Syria would be weak in the present situation even if the Israelis weren’t contributing to its travail. But Netanyahu’s policy is to burn down his neighbors’ houses. He has done it in Gaza, Lebanon, and now Syria. He would no doubt like to do the same in Yemen. Jordan is already a client state, as the monarchy owes its continued existence to Israeli security cooperation. Egypt is likewise neutralized, even if uncomfortable with Israel’s behavior in Gaza. Netanyahu’s aim is a regionally hegemonic Greater Israel. He wants full control over the West Bank and Gaza and cowed enemies in Lebanon and Syria. For now, he is succeeding.

The fight for justice in a post-Assad Syria

Colleagues at the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) have posted this statement welcoming the fall of the Assad regime and looking ahead to a just outcome:

Thirteen years ago, SJAC began preparing for the day after the fall of the Assad government, with the steadfast belief that Syrians would someday have an opportunity to pursue meaningful justice and accountability for the crimes committed against them and to build a state that respects the rights of all Syrians.

Over the past decade, our team in Syria and across the diaspora have collected over two million pieces of documentation of the conflict, conducted extensive investigations of international crimes, and laid the groundwork for comprehensive missing persons investigations. Now, at the start of the first week of a post-Assad Syria, our work has just begun.

In the coming weeks, SJAC’s team will be focused on collecting and preserving at-risk documentation from previously inaccessible, government-controlled areas while ensuring that Syrians have access to clear, impartial sources of information on the immediate justice challenges that will arise in the coming days. As the situation on the ground stabilizes, our team looks forward to working alongside Syrians from across the country to begin to design a meaningful transitional justice process.

While SJAC has long supported Syrian-led justice, the dream of a stable and peaceful Syria can only be achieved with the support of the international community. Over the past decade, as the conflict stalled, many states have withdrawn support for human rights and humanitarian efforts in Syria, while simultaneously disengaging in the peace process. Now, with the dream of a stable and peaceful Syrian at hand, we ask that the international community re-engage in Syria, both through robust funding for reconstruction and justice processes, as well as through political engagement.

As the political makeup of a post-Assad Syria evolves, the international community should reconsider sanctions and reassess Hayat Tahrir Al Sham’s designation as a terrorist organization. In a time of uncertainty, we also ask that host countries continue to provide safe asylum to Syrians around the globe. Syrians themselves will be best placed to assess when it is safe to return.

The future may be uncertain, but the SJAC team is excited to have the opportunity to work for justice and accountability in a post-Assad Syria.

Winners and losers from Assad’s fall

The success of Syrians in deposing Bashar al Assad poses the question of who wins and who loses. Inside Syria, Hayat Tahrir al Sham is the big winner for now. It led the breakout from Idlib and inspired the many risings elsewhere in Syria.

There are lots of other countries that stand to win or lose something in the transition. Let’s assume Syria remains reasonably stable and its government basically inclusive and not vindictive, which appears to be HTS’ intention. We can try to guess the pluses and minuses for the rest of the world.

Turkiye is the big winner

In the region, Turkiye is the big winner. President Erdogan had been ready to negotiate with Assad, who refused to engage. Erdogan lost patience and backed a military outcome. He unleashed both Turkish proxies and HTS, which could not have armed and equipped itself adequately without Ankara’s cooperation. He does not control HTS 100%, especially now that it is in Damascus. But he will have a good deal of influence over its behavior. Let’s hope he uses it in the democratic and less religious direction. That however is the opposite of what he has been doing at home.

Erdogan has two primary goals in Syria. First is achieving enough stability there to allow many of the three million Syrian refugees in Turkiye to return. Returns will take time, but there is already a spontaneous flow back into Syria. The second is keeping the Syrian Kurds associated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) away from Turkiye’s border with Syria. Erdogan would also like its Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) dissolved. Or at least as far from power as possible.

Refugee returns look like a good bet. Disempowering the Kurds in eastern and northern Syria does not. They are well-established and cooperate closely with US forces in that area. Future President Trump will want to withdraw the Americans. But the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces will remain essential to fighting the Islamic State (IS). HTS, IS, and the PKK all carry the “terrorist” label in the US and Europe. But HTS and IS are rivals. HTS will want the Kurds to continue to fight IS. They will also be vital, at least temporarily, to preventing Iran from re-establishing a land route through Syria to Lebanon.

Israel wins and loses

The Israeli government would have preferred to see the Assad devil it knew stay in power. But his fall means the Iranians and their proxies will no longer be stationed along the northeastern border of Israel. The Israelis have already moved their troops into a UN-patrolled buffer zone inside Syria. They didn’t want some known or unknown force filling that vacuum. That advance might give them a stronger position in future negotiations with Damascus, whenever those occur.

But Israelis have to be worried that a jihadist group led the overthrow of Assad. Ahmed al Sharaa, the birth name of HTS’s Abu Mohammed al Jolani, was born in Riyadh to Syrian parents. They were displaced from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. The second Palestinian intifada motivated his conversion to jihad. It is hard to picture someone with that background more pliable than the impacable Assad on border and Palestinian issues. Jolani himself appears to have said little about Gaza or the Lebanon war. But some of his followers are clear about where they want to go next:

Lebanon and Jordan

Lebanon and Jordan, two key neighbors of Syria, can hope to be winners from the change of regime . Both will want to see Syrian refugees return home, as they were a strain on their economies. They will also stand to gain from reconstruction and eventually a more prosperous Syria.

Assad had been financing his government and his cronies with proceeds from the export of the stimulant Captagon. Decent people in both Beirut and Amman will welcome relief from that flood of poison into and through their societies. Some of their corrupted politicians may regret it.

Lebanon will have to reabsorb Hezbollah fighters who supported Assad. They will be a defeated and unhappy lot. But the Lebanese Army and state stand to gain from any weakening and demoralization of Hezbollah. Anyone serious in Beirut should see the current situation as an opportunity to strengthen both.

Iran and Russia are the biggest losers

Apart from Assad, Tehran and Moscow are the biggest losers. They backed Assad with people, force, money, and diplomacy. They are now thoroughly discredited.

Iran has already evacuated its personnel from Syria. Tehran has lost not only its best ally but also its land route to Lebanon.

Russia still has its bases. Almost any future Syrian government will have a hard time seeing what it gains from the Russian air force presence. Moscow’s air force brutalized Syrian civilians for almost 10 years. The air bases will no longer have utility even to Moscow. Moscow will prioritize keeping the naval base at Tartus, which is important for its Mediterranean operations.

The Gulf gains, Iraq loses

Gulf diplomacy was trying to normalize relations with Assad in the past year or two. But few Gulfies will mourn his regime, provided stability is maintained. Qatar may be more pleased than Saudi Arabia or Abu Dhabi. The Saudis and Emiratis are less tolerant of political Islam. Nor do they like to see regimes fall. Qatar is more comfortable with political change, including of the Islamist variety.

Iraq’s Shia-dominated government loses a companion in Damascus. It won’t welcome a Sunni-dominated government in Damascus. But Baghdad, like the Gulf, is unlikely to mourn the fall of Assad. He did his damnedest to make life difficult for Iraqis after the fall of Saddam Hussein.

The United States and Europe gain but will need to ante up

The US and Europe have long viewed Assad as a regrettable but necessary evil. They hesitated to bring him down for fear of what might come next. Now they need to step up and fund Syria’s recovery, mainly through the IMF and the World Bank. They will want Gulf money invested as well. The best way to get that is for them to ante up matching funds.

That is also the best way for them to gain leverage over the political settlement. If they want an inclusive outcome, they’ll need to be ready to pay for it. Hesitation could open the door to malicious influence.

Let the Syrians decide

That said, the details of the political settlement should be left to the Syrians. They will need to write a new constitution and eventually hold elections. The extensive constitutional discussions the UN has hosted for a decade may offer some enlightenment on what Syrians want. Just as important in my view is how the new powers that be handle property issues. Only if property rights are clearly established and protected can Syria’s economy revive. But who rightfully owns what and what to do about destroyed property are complicated and difficult issues.

Will Syria stay together or fragment?

One of the threats to Syria now that Assad has fallen is fragmentation. In my experience, all Syrians say they want to preserve the country and its borders. But the conflicts among them and with neighboring countries can foil that goal and lead to partition.

The pieces of the puzzle

Syria’s population is mixed. Ninety per cent of its population is Arab. The rest is mainly Kurdish and Turkmen. More than 70% of Syrians are Sunni Muslim. But there are also various denominations of Christians as well as Alawites, Druze, Ismailis, Shiites and others. Damascus was thoroughly mixed. Several concentrations of Kurds were found along the northern border with Turkey, along with Turkmen and Arabs. The Alawite “homeland” was in the western, Mediterranean provinces of Tartous and Latakis. But they were a plurality and not a majority there. More Sunnis have sought refuge there, as under Bashar al Assad, an Alawite, those provinces were relatively safe.

The war is superimposing on this hodge-podge an additional dimension: military control of territory. Hayat Tahrir al Sham, the leader of the uprising, will control much of Idlib, Aleppo, Hama, and Homs. Turkey and its surrogates will control most of the northern border. They are trying to push Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) east of the Euphrates, an area the SDF already dominates. Other opposition forces will be in charge of the south and the Jordanian border. The Druze have long maintained their insular community in Suwayda. It is unclear who will dominate Damascus. The southerners are arriving there first, but it is hard to picture HTS settling for second fiddle there.

There are no clear pre-existing regional lines along which Syria might fragment, except for the provincial boundaries. But those do not generally correspond to ethnic or religious divisions. The pieces of the puzzle do not fit together. They overlap and melt into each other.

The divisive forces

That would be a good reason to avoid fragmentation. Homogenization of ethnic groups on specific territory would require an enormous amount of ethnic “cleansing.” Ordinary Syrians don’t want that. But there will be forces at work that might make it happen.

The Turkmen/Kurdish conflict has already removed a lot of Kurds from Afrin in the northwest and border areas farther east. Ankara backs the Turkmen and wants to prevent Kurdish access to Türkiye. This is because the Syrian Kurds have supported Kurdish rebels inside Türkiye. The Kurds have built their own governing institutions in eastern Syria. They might seek independence if they get an unsatisfactory political outcome at the end of the war.

The Alawites of Tartous and Latakia are dreading revenge from the rest of Syria for mistreatment under the Assad dictatorship. They could try to set up their own statelet, perhaps even attaching it to Lebanon. They could also try to chase the Sunni Arab population out, while importing as many Alawites as possible from Damascus. Many there served the Assad regime and will want out.

The unifying forces

Syria’s neighbors won’t want a breakup. Türkiye has the most clout because of its presence in Syria and support for HTS. Ankara will oppose even autonomy for the Kurds. Jordan and Iraq have less clout, but they won’t want fragmentation either. Nor will Russia and Iran, which supported Assad and are big losers due to his fall. Ditto Israel and the United States, which would fear radicalization of any rump Syria if its Kurds or Alawites secede. Israel doesn’t want a jihadist entity on its northern border.

HTS and other opposition forces will also resist fragmentation. They want to govern all of Syria, not a part of it. HTS has moderated its attitude toward non-Arab and non-Sunni Muslims. It has also tried to minimize revenge and has emphasized continuity of the Syrian state. But HTS is an authoritarian movement, not a democratic one. It remains to be seen how it will behave in practice.

The obvious solutions

The obvious solution is decentralization. Devolving authority to provincial and municipal institutions offers minorities opportunities to govern themselves, or strongly influence how they are governed. The Alawites and Kurds might be satisfied with decentralization, provided they also get reasonable representation at the national level. The Kurds already have their own institutions. Some non-Kurdish opposition areas in Syria have used local councils for governance since the 2011 uprising against Assad.

There are also power-sharing arrangements that can assuage minority concerns at the national level and lower levels. Quotas in parliament, reserved positions in the state hierarchy, and qualified majority voting in parliament or local councils. I’m not an enthusiast for these, as they often entrench ethnic warlords, but sometimes they prove necessary.

Syrians may invent mechanisms I haven’t considered. In any event it is they who should decide. The country will need a new constitution, then in due course elections. The existing road map for Syria’s political process is UN Security Council resolution 2254, which Assad stymied. HTS and the rest of the opposition can revive it and gain international support by doing so.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts