Reconciliation: a new vision for OSCE?

I am speaking at the OSCE “Security Days” today in Vienna on a panel devoted to this topic. Here is what I plan to say, more or less:

Reconciliation is hard. Do I want to be reconciled to someone who has done me harm? I may want an apology, compensation, an eye for an eye, but why would I want to be reconciled to something I regard as wrong, harmful, and even evil?

At the personal level, I may be able to escape the need for reconciliation. I can harbor continuing resentment, emigrate, join a veterans’ organization and continue to dislike my enemy. I can hope that my enemy is prosecuted for his crimes and is sent away for a long time. I don’t really have to accept his behavior. Many don’t.

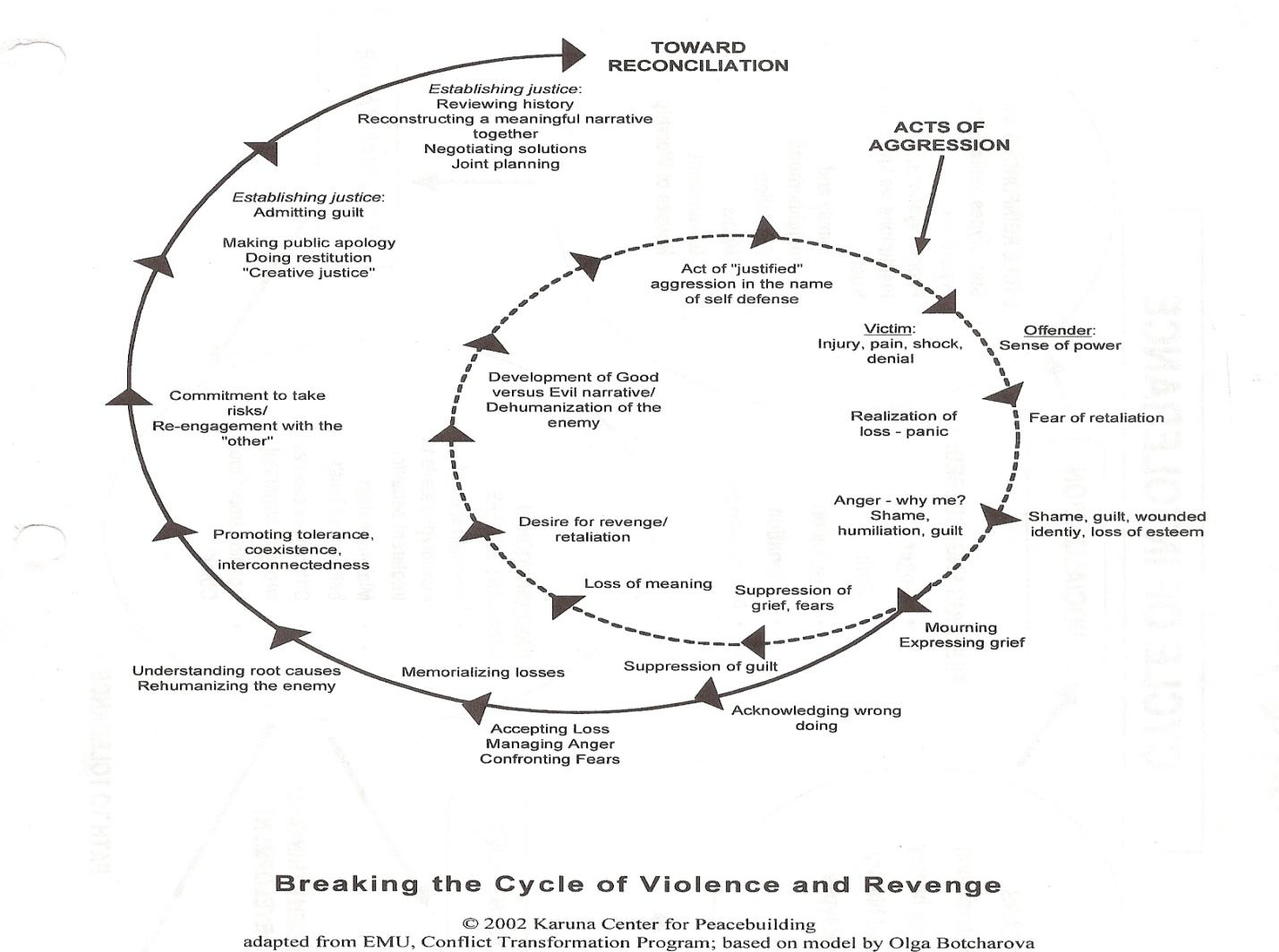

But at the societal level lack of reconciliation has consequences. It is a formula for more violence. We remain trapped in the inner circle of this classic diagram, in a cycle of violence. Victims, feeling loss and desire for revenge, end up attacking those they believe to be perpetrators, who eventually react with violence:

What takes us out of the cycle of violence and retaliation? The critical step is acknowledging wrong doing, a step full of risk for perpetrators and meaning for victims. But once wrong doing is acknowledged, victims can begin to accept loss, manage anger and confront fears. This initiates a virtuous cycle of mutual understanding, re-engagement, admission of guilt, steps toward justice and writing a common history.

What has all this got to do with OSCE? Some OSCE countries are still stuck in the inner cycle of violence, despite dialogue focused on practical confidence-building measures that moves the parties closer. But the vital step of acknowledging wrong has either been skipped entirely or given short shrift. Conflict management is a core OSCE function. The job will not be complete until OSCE re-discovers its role in reconciliation.

I know the Balkans best. We aren’t past the step of acknowledging wrongdoing in Bosnia and Kosovo. Even Greece and Macedonia are trapped in a cycle that could become violent. The situation is less than fully reconciled in Turkey, the Caucasus, Moldova and I imagine other places I know less well. Is there a good example of Balkans reconciliation? The best I know is Montenegro’s apology to Croatia for shelling Dubrovnik. That allowed them to build the positive relationship they have today.

Should reconciliation be a new OSCE vision? Its leadership and member states will decide, but here are questions I would ask if I were considering the proposition:

- How pervasive is the need for reconciliation in the OSCE?

- Would it make a real difference if reconciliation could be established as a norm?

- If it did become a new norm, how would we know when it is achieved?

- What would we do differently from what we do today?

I was in Kosovo earlier this month. There is little sign there of reconciliation: it is difficult for Belgrade and Pristina to talk with each other, they have reached agreements under pressure that are largely unimplemented, OSCE and other international organizations maintain operations there because of the risk of violence. There is little acknowledgement of wrong doing. The memorials are all one-sided: I drove past many well-marked KLA graveyards. We have definitely not reached the outer circle yet.

Would it make a difference if there were acknowledgement of wrong doing? Yes, it would. It would have to be mutual, since a good deal of harm has been done on both sides, even if the magnitude of the harm differs. Self-sustaining security in Kosovo will not be possible until that step has been taken. I would say the same thing about Bosnia, Kyrgystan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey and Armenia. Your North African partners might benefit from focus on reconciliation.

Dialogue is good. Reconciliation is better. Maybe OSCE should take the next difficult but logical step.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts