Tag: Georgia

This week’s peace picks

There is far too much happening Monday and Tuesday in particular. But here are this week’s peace picks, put together by newly arrived Middle East Institute intern and Swarthmore graduate Allison Stuewe. Welcome Allison!

1. Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: Political Progress in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Monday September 10, 10:00am-12:00pm, Johns Hopkins SAIS

Venue: Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, The Bernstein-Offit Building, 1740 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036, Room 500

Speaker: Patrick Moon

In June 2012, the governing coalition in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had taken eighteen months to construct, broke up over ratification of the national budget. In addition, there has been heated debate over a proposed electoral reform law and the country’s response to a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights. Party leaders are once again jockeying for power, and nationalist rhetoric is at an all-time high in the run-up to local elections in early October.

Register for this event here.

2. Just and Unjust Peace, Monday September 10, 12:00pm-2:00pm, Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, & World Affairs

Venue: Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, & World Affairs, 3307 M Street, Washington, DC 20007, 3rd Floor Conference Room

Speakers: Daniel Philpott, Mohammed Abu-Nimer, Lisa Cahill, Marc Gopin

What is the meaning of justice in the wake of massive injustice? Religious traditions have delivered a unique and promising answer in the concept of reconciliation. This way of thinking about justice contrasts with the “liberal peace,” which dominates current thinking in the international community. On September 14th, the RFP will host a book event, responding to Daniel Philpott’s recently published book, Just and Unjust Peace: A Ethic of Political Reconciliation. A panel of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars will assess the argument for reconciliation at the theological and philosophical levels and in its application to political orders like Germany, South Africa, and Guatemala.

Register for this event here.

3. The New Struggle for Syria, Monday September 10, 12:00pm-2:00pm, George Washington University

Venue: Lindner Family Commons, 1957 E Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, Room 602

Speakers: Daniel L. Byman, Gregory Gause, Curt Ryan, Marc Lynch

Three leading political scientists will discuss the regional dimensions of the Syrian conflict.

A light lunch will be served.

Register for this event here.

4. Impressions from North Korea: Insights from two GW Travelers, Monday September 10, 12:30pm-2:00pm, George Washington University

Venue: GW’s Elliot School of International Affairs, 1957 E Street NW, Washington, DC 20052, Room 505

Speakers: Justin Fisher, James Person

The Sigur Center will host a discussion with two members of the GW community who recently returned from North Korea. Justin Fisher and James F. Person will discuss their time teaching and researching, respectively, in North Korea this Summer and impressions from their experiences. Justin Fisher spent a week in North Korea as part of a Statistics Without Borders program teaching statistics to students at Pyongyang University of Science and Technology. James Person recently returned from a two-week trip to North Korea where he conducted historical research.

Register for this event here.

5. America’s Role in the World Post-9/11: A New Survey of Public Opinion, Monday September 10, 12:30pm-2:30pm, Woodrow Wilson Center

Venue: Woodrow Wilson Center, 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20004, 6th Floor, Joseph H. and Claire Flom Auditorium

Speaker: Jane Harman, Marshall Bouton, Michael Hayden, James Zogby, Philip Mudd

This event will launch the latest biennial survey of U.S. public opinion conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, and is held in partnership with them and NPR.

RSVP for this event to rsvp@wilsoncenter.org.

6. Transforming Development: Moving Towards an Open Paradigm, Monday September 10, 3:00pm-4:30pm, CSIS

Venue: CSIS, 1800 K Street NW, Washington, DC 20006, Fourth Floor Conference Room

Speakers: Ben Leo, Michael Elliott, Daniel F. Runde

Please join us for a discussion with Mr. Michael Elliot, President and CEO, ONE Campaign, and Mr. Ben Leo, Global Policy Director, ONE Campaign about their efforts to promote transparency, openness, accountability, and clear results in the evolving international development landscape. As the aid community faces a period of austerity, the panelists will explain how the old paradigm is being replaced by a new, more open, and ultimately more effective development paradigm. Mr. Daniel F. Runde, Director of the Project on Prosperity and Development and Schreyer Chair in Global Analysis, CSIS will moderate the discussion.

RSVP for this event to ppd@csis.org.

7. Campaign 2012: War on Terrorism, Monday September 10, 3:30pm-5:00pm, Brookings Institution

Venue: Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036, Falk Auditorium

Speakers: Josh Gerstein, Hafez Ghanem, Stephen R. Grand, Benjamin Wittes

With both presidential campaigns focused almost exclusively on the economy and in the absence of a major attack on the U.S. homeland in recent years, national security has taken a back seat in this year’s presidential campaign. However, the administration and Congress remain sharply at odds over controversial national security policies such as the closure of the Guantanamo Bay detention facility. What kinds of counterterrorism policies will effectively secure the safety of the United States and the world?

On September 10, the Campaign 2012 project at Brookings will hold a discussion on terrorism, the ninth in a series of forums that will identify and address the 12 most critical issues facing the next president. White House Reporter Josh Gerstein of POLITICO will moderate a panel discussion with Brookings experts Benjamin Wittes, Stephen Grand and Hafez Ghanem, who will present recommendations to the next president.

After the program, panelists will take questions from the audience. Participants can follow the conversation on Twitter using hashtag #BITerrorism.

Register for this event here.

8. Democracy & Conflict Series II – The Middle East and Arab Spring: Prospects for Sustainable Peace, Tuesday September 11, 9:30am-11:00am, Johns Hopkins SAIS

Venue: Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, ROME Building, 1619 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036

Speaker: Azizah al-Hibri, Muqtedar Khan, Laith Kubba, Peter Mandaville, Joseph V. Montville

More than a year and a half following the self-immolation of a street vendor in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia, Arab nations are grappling with the transition toward sustainable peace. The impact of the Arab Spring movement poses challenges for peaceful elections and establishing stable forms of democratic institutions. This well-versed panel of Middle East and human rights experts will reflect on the relevance and role of Islamic religious values and the influence of foreign policy as democratic movements in the Middle East negotiate their futures.

Register for this event here.

9. Israel’s Security and Iran: A View from Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, Tuesday September 11, 9:30am-11:00am, Brookings Institution

Venue: Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Ave NW, Washington, DC 20036, Falk Auditorium

Speakers: Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, Kenneth M. Pollack

While Israel and Iran continue trading covert punches and overheated rhetoric, the question of what Israel can and will do to turn back the clock of a nuclear Iran remains unanswered. Some Israelis fiercely advocate a preventive military strike, while others press just as passionately for a diplomatic track. How divided is Israel on the best way to proceed vis-à-vis Iran? Will Israel’s course put it at odds with Washington?

On September 11, the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings will host Lt. Gen. Dan Haloutz, the former commander-in-chief of the Israeli Defense Forces, for a discussion on his views on the best approach to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Brookings Senior Fellow Kenneth Pollack will provide introductory remarks and moderate the discussion.

After the program, Lt. Gen. Haloutz will take audience questions.

Register for this event here.

10. Montenegro’s Defense Reform: Cooperation with the U.S., NATO Candidacy and Regional Developments, Tuesday September 11, 10:00am-11:30am, Johns Hopkins SAIS

Venue: Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, 1625 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036, Room 211/212

Montenegro has been one of the recent success stories of the Western Balkans. Since receiving a Membership Action Plan from NATO in December 2009, in close cooperation with the U.S. it has implemented a series of defense, political, and economic reforms, which were recognized in the Chicago Summit Declaration in May 2012 and by NATO Deputy Secretary General Vershbow in July 2012. Montenegro contributes to the ISAF operation in Afghanistan and offers training support to the Afghan National Security Forces. In June 2012 it opened accession talks with the European Union.

Register for this event here.

11. Inevitable Last Resort: Syria or Iran First?, Tuesday September 11, 12:00pm-2:00pm, The Potomac Institute for Policy Studies

Venue: The Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, 901 N. Stuart Street, Arlington, VA 22203, Suite 200

Speakers: Michael S. Swetnam, James F. Jeffrey, Barbara Slavin, Theodore Kattouf, Gen Al Gray

Does the expanding civil war in Syria and its grave humanitarian crisis call for immediate international intervention? Will Iran’s potential crossing of a nuclear weapon “red line” inevitably trigger unilateral or multilateral military strikes? Can diplomacy still offer urgent “honorable exit” options and avoid “doomsday” scenarios in the Middle East? These and related issues will be discussed by both practitioners and observers with extensive experience in the region.

RSVP for this event to icts@potomacinstitute.org or 703-562-4522.

12. Elections, Stability, and Security in Pakistan, Tuesday September 11, 3:30pm-5:00pm, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Venue: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 1779 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20036

Speakers: Frederic Grare, Samina Ahmed

With the March 2013 elections approaching, the Pakistani government has an opportunity to ensure a smooth transfer of power to the next elected government for the first time in the country’s history. Obstacles such as a lack of security, including in the tribal borderlands troubled by militant violence, and the need to ensure the participation of more than 84 million voters threaten to derail the transition. Pakistan’s international partners, particularly the United States, will have a crucial role in supporting an uninterrupted democratic process.

Samina Ahmed of Crisis Group’s South Asia project will discuss ideas from her new report. Carnegie’s Frederic Grare will moderate.

Register for this event here.

13. Islam and the Arab Awakening, Tuesday September 11, 7:00pm-8:00pm, Politics and Prose

Venue: Politics and Prose, 5015 Connecticut Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20008

Speaker: Tariq Ramadan

Starting in Tunisia in December 2010, Arab Spring has changed the political face of a broad swath of countries. How and why did these revolts come about–and, more important, what do they mean for the future? Ramadan, professor of Islamic Studies at Oxford and President of the European Muslim Network, brings his profound knowledge of Islam to bear on questions of religion and civil society.

14. Beijing as an Emerging Power in the South China Sea, Wednesday September 12, 10:00am, The House Committee on Foreign Affairs

Venue: The House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 2170 Rayburn House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515

Speakers: Bonnie Glaser, Peter Brookes, Richard Cronin

Oversight hearing.

15. The Caucasus: A Changing Security Landscape, Thursday September 13, 12:30pm-4:30pm, CSIS

Venue: CSIS, 1800 K Street NW, Washington, DC 20006, B1 Conference Center

Speakers: Andrew Kuchins, George Khelashvili, Sergey Markedonov, Scott Radnitz, Anar Valiyey, Mikhail Alexseev, Sergey Minasyan, Sufian Zhemukhov

The Russia-Georgia war of August 2008 threatened to decisively alter the security context in the Caucasus. Four years later, what really has changed? In this conference, panelists assess the changing relations of the three states of the Caucasus — Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan — with each other and major neighbors, Russia and Iran. They also explore innovative prospects for resolution in the continued conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia and the possibility of renewed hostilities over Nagorno-Karabakh. This conference is based on a set of new PONARS Eurasia Policy Memos, which will be available at the event and online at www.ponarseurasia.org. Lunch will be served.

RSVP for this event to REP@csis.org.

16. Author Series Event: Rajiv Chandrasekaran, “Little Afghanistan: The War Within the War for Afghanistan”, Thursday September 13, 6:30pm-8:30pm, University of California Washington Center

Venue: University of California Washington Center, 1608 Rhode Island Ave NW, Washington, DC 20036

Speaker: Rajiv Chandrasekaran

In the aftermath of the military draw-down of US and NATO forces after over ten years in Afghanistan, examinations of US government policy and efforts have emerged. What internal challenges did the surge of US troops encounter during the war? How was the US aiding reconstruction in a region previously controlled by the Taliban?

Rajiv Chandrasekaran will discuss his findings to these questions and US government policy from the perspective of an on-the-ground reporter during the conflict. This forum will shed light on the complex relationship between America and Afghanistan.

Register for this event here.

Reconciliation: a new vision for OSCE?

I am speaking at the OSCE “Security Days” today in Vienna on a panel devoted to this topic. Here is what I plan to say, more or less:

Reconciliation is hard. Do I want to be reconciled to someone who has done me harm? I may want an apology, compensation, an eye for an eye, but why would I want to be reconciled to something I regard as wrong, harmful, and even evil?

At the personal level, I may be able to escape the need for reconciliation. I can harbor continuing resentment, emigrate, join a veterans’ organization and continue to dislike my enemy. I can hope that my enemy is prosecuted for his crimes and is sent away for a long time. I don’t really have to accept his behavior. Many don’t.

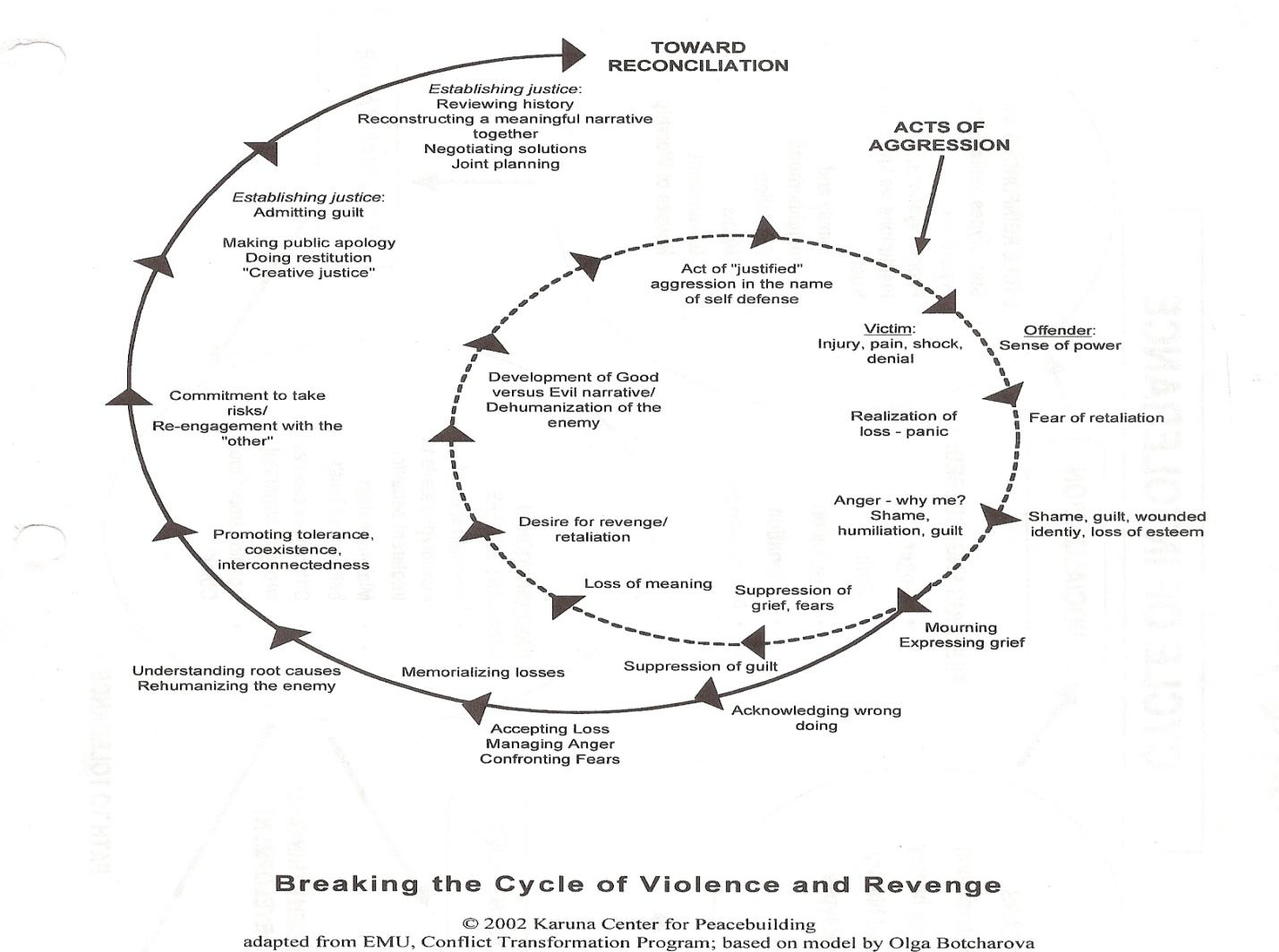

But at the societal level lack of reconciliation has consequences. It is a formula for more violence. We remain trapped in the inner circle of this classic diagram, in a cycle of violence. Victims, feeling loss and desire for revenge, end up attacking those they believe to be perpetrators, who eventually react with violence:

What takes us out of the cycle of violence and retaliation? The critical step is acknowledging wrong doing, a step full of risk for perpetrators and meaning for victims. But once wrong doing is acknowledged, victims can begin to accept loss, manage anger and confront fears. This initiates a virtuous cycle of mutual understanding, re-engagement, admission of guilt, steps toward justice and writing a common history.

What has all this got to do with OSCE? Some OSCE countries are still stuck in the inner cycle of violence, despite dialogue focused on practical confidence-building measures that moves the parties closer. But the vital step of acknowledging wrong has either been skipped entirely or given short shrift. Conflict management is a core OSCE function. The job will not be complete until OSCE re-discovers its role in reconciliation.

I know the Balkans best. We aren’t past the step of acknowledging wrongdoing in Bosnia and Kosovo. Even Greece and Macedonia are trapped in a cycle that could become violent. The situation is less than fully reconciled in Turkey, the Caucasus, Moldova and I imagine other places I know less well. Is there a good example of Balkans reconciliation? The best I know is Montenegro’s apology to Croatia for shelling Dubrovnik. That allowed them to build the positive relationship they have today.

Should reconciliation be a new OSCE vision? Its leadership and member states will decide, but here are questions I would ask if I were considering the proposition:

- How pervasive is the need for reconciliation in the OSCE?

- Would it make a real difference if reconciliation could be established as a norm?

- If it did become a new norm, how would we know when it is achieved?

- What would we do differently from what we do today?

I was in Kosovo earlier this month. There is little sign there of reconciliation: it is difficult for Belgrade and Pristina to talk with each other, they have reached agreements under pressure that are largely unimplemented, OSCE and other international organizations maintain operations there because of the risk of violence. There is little acknowledgement of wrong doing. The memorials are all one-sided: I drove past many well-marked KLA graveyards. We have definitely not reached the outer circle yet.

Would it make a difference if there were acknowledgement of wrong doing? Yes, it would. It would have to be mutual, since a good deal of harm has been done on both sides, even if the magnitude of the harm differs. Self-sustaining security in Kosovo will not be possible until that step has been taken. I would say the same thing about Bosnia, Kyrgystan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey and Armenia. Your North African partners might benefit from focus on reconciliation.

Dialogue is good. Reconciliation is better. Maybe OSCE should take the next difficult but logical step.

Democracy fails between elections

Newly arrived Middle East Institute summer intern Ilona Gerbakher writes:

While the world is significantly more democratic today than it was twenty years ago, there have been notable failed transitions. Political scientists Danielle Lussier and Jody Laporte gave a joint talk Tuesday at the Woodrow Wilson Center on “The Failure of Democracy in Post-Soviet Eurasia.” Lussier focused on the regression to authoritarian rule in Russia under Vladimir Putin. Laporte investigated the ways in which three post-Soviet authoritarian regimes – Georgia, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan – deal with political opposition between elections. Lussier and Laporte chart the decline of freedom in former communist countries, and ask the question, “why did democracy fail to survive in Russia and the Eurasian republics?”

The case of Russia is perplexing, as it is an outlier in the context of democratization theory. Its level of wealth, education and history of independent statehood suggest Russia should be more politically open than it is today. Lussier presented a graph which showed that, since 1998, Russia’s domestic policies have been backsliding into authoritarian territory. Examples of this backsliding include passage of laws that have obstructed the formation of political parties, cancellation of elections and legislation that curtails freedoms of press and association.

Lussier rejects the three common explanations for the return to authoritarianism in Russia. First of these is that Russia’s elite is insulated from popular pressure by hydrocarabon wealth. Second is that Russia’s history instilled a cultural preference for authoritarian rule. Third is that the failure of liberalization in the 1990’s discredited democracy in Russia.

She suggests an alternative explanation: that the Russian public failed to constrain the Russian political elite. Elite constraining activities, such as building and supporting opposition parties and campaigns as well as public acts of political dissent, are a vital check on the tendency of governments to centralize power in economically or politically difficult periods. The Russian public more consistently engages in elite-enabling activities that support hegemonic parties.

One elite-enabling activity, contacting public officials to perform private favors, is the single (non-voting) political activity with the highest public participation. Other forms of non-voting political participation have steadily declined for the last two decades. They are episodic rather than repetitive. Young people are the least politically engaged sector of society. The decline in political participation preceded the decline in political openness (and the rise of authoritarianism) in Russia.

Laporte shifted the focus from Russia to Georgia, Azerbaijan and Kazakstan. Twenty years after the fall of the Soviet Union, the only post-Soviet democracies are Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The rest are non-democracies, because vote fraud and voter manipulation is endemic. Elections are neither free nor fair. In order to investigate the inner-working of these authoritarian regimes, Laporte examined the way that they treat political opposition between, as well as during, elections.

In all three countries, the election committees are dominated by pro-government officials, state resources are abused in order to mobilize support for the government, and vote fraud is endemic. Opposition parties are prevented from registration in various ways, their space for campaigning is limited, and opposition party operatives are often harassed.

Between election cycles differences emerge. In Kazakhstan, repression of opposition parties is constant and unconditional. All opposition groups and operatives are targeted, the dominant tactic is violent repression, and the goal of the government seems to be to completely eradicate the opposition. In Georgia, repression of opposition parties between elections is intermittent, the targets are random, the dominant tactic of repression is public and private criticism by government officials (acts of violence against opposition groups are rare), and the intent seems to be harassment rather then eradication of the opposition. In Azerbaijan, repression of opposition parties is reactive and the targets are contingent upon circumstances, with more opposition parties are being targeted in recent years. The main goal is to discourage criticism of the government. The dominant tactic is judicial, such as high court fines levied against protestors. Why do we see these differences in the treatment of opposition groups? Laporte speculates that both the nature of the opposition party and patterns of political corruption are at play.

Goat rope

I arrived in Pristina yesterday and have enjoyed two days of intense conversations about Kosovo’s international relations, which are enormously complex for a country of less than 1.8 million inhabitants.

Let’s review the bidding. Kosovo declared independence in 2008, after almost nine years of UN administration following the 1999 NATO/Yugoslavia war. Serbia, of which Kosovo was at one time a province, did not concur in independence and has not recognized the Kosovo state’s sovereignty. But 90 other countries have, including the United States and 22 of the 27 members of the European Union (EU) and 24 of 28 members of NATO. Russia has blocked approval of UN membership in the Security Council, at the behest of Serbia. An International Civilian Office (ICO) will supervise Kosovo’s independence until September, when it plans to certify that the Kosovo government has fulfilled its responsibilities under the international community “Ahtisaari plan” (the Comprehensive Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement). That was intended to be the agreement under which Kosovo became independent but was implemented unilaterally (under international community pressure) by the Kosovo government when Serbia refused to play ball. Belgrade and Pristina talk, but almost exclusively in an EU-facilitated and US-supported dialogue limited to resolution of technical, not political, issues.

Even after the ICO closes, Kosovo will be under intense international scrutiny (for a fuller account, see the Kosovar Center for Security studies report). NATO provides a safe and secure environment and is training its security forces for their enhanced roles after the July 2013. An EU rule of law mission monitors Kosovo’s courts and provides international investigators, prosecutors and judges for interethnic cases. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) provides training and advice on democratization, human and minority rights. The Council of Europe (CoE) administers programs on cultural and archaelogical heritage, social security co-ordination and cybercrime. The UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) continues despite its inconsistency with both the Ahtisaari plan and the declaration of independence, which at Serbia’s behest the International Court of Justice has advised was not in violation of international law or UN Security Council resolution 1244 (which established UNMIK).

Kosovo’s many complications get even worse north of the Ibar river, in the 11% of the country’s territory contiguous with Serbia that is still not under Pristina’s control. It may not really be under Belgrade’s control either, but that makes the situation there even more difficult. Partition of that northern bit, which Belgrade authorities have pursued, would likely precipitate ethnic partitions in other parts of the Balkans: Macedonia, Bosnia and Cyprus would all be at risk if Kosovo were split, an outcome neither Europe nor the U.S. wants to face. Serbia’s President-elect Nikolic suggested last week that Belgrade might recognize the Georgian break-away regions of South Ossetia and Abhazia, a move that would simultaneously deprive Serbia of its heretofore principled stance against Kosovo independence but at the same time reinforce Belgrade’s hope for partition of northern Kosovo.

What we’ve got here is a goat rope, as the U.S. military says. The situation seems hopelessly tangled. It is a miracle that the Kosovo government gets anything done with so many foreigners people looking over its shoulders. It naturally also has to meet domestic expectations, which are increasingly in the direction of more independence and fewer non-tourist foreigners, though Americans seem always to get a particularly warm welcome because of their role in past efforts to protect Kosovo from the worst ravages of Slobodan Milošević.

Kosovo unquestionably continues to need help. OSCE recently organized Serbian presidential elections in the Serb communities of Kosovo, a task that would have proven impossible for the Pristina or the Belgrade authorities. NATO has a continuing role because it will be some years yet before Kosovo can defend itself for even a week from a Serbian military incursion, which is unlikely but cannot be ruled out completely until Belgrade recognizes the Kosovo authorities as sovereign. The Kosovo courts would still find it difficult to have their decisions fully accepted in many cases of interethnic crime.

But the time is coming this fall for this overly supervised country to struggle on its own, making a few mistakes no doubt but also holding its authorities responsible for them. Kosovo needs a foreign policy that will take it to the next level. That means not only untangling the goat rope (or occasionally cutting through it) but also achieving normal relations with Belgrade and UN membership. There is no reason that an intense effort over the next decade cannot take Kosovo into NATO and perhaps even into the EU, or close to that goal, provided it treats its Serb and other minority citizens correctly and resolves the many outstanding issues with Belgrade on a reciprocal basis, and peacefully.

This week’s “peace picks”

Loads of interesting events this week:

1. Georgian-South Ossetian Confidence Building Processes, Woodrow Wilson Center, 6th floor, February 6, noon- 1pm

Dr. Susan Allen Nan will discuss the Georgian-South Ossetian relationship, including insights from the 14 Georgian-South Ossetian confidence building workshops she has convened over the past three years, the most recent of which was in January. The series of unofficial dialogues catalyze other confidence building measures and complement the Geneva Talks official process.

Please note that seating for this event is available on a first come, first served basis. Please call on the day of the event to confirm. Please bring an identification card with a photograph (e.g. driver’s license, work ID, or university ID) as part of the building’s security procedures.

The Kennan Institute speaker series is made possible through the generous support of the Title VIII Program of the U.S. Department of State.

-

Associate Professor of Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University

by

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Former National Security Adviser and CSIS Counselor and Trustee

Willard Room, Willard InterContinental Hotel

1401 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC

Introduction by

John Hamre, CSIS

Remarks by

Zbigniew Brzezinski

Interviewed by

David Ignatius, The Washington Post

Book Signing

from 4:00 to 4:30 p.m.

-Books will be available for purchase-

This invitation is non-transferable. Seating is limited.

To RSVP please e-mail externalrelations@csis.org by Wednesday, February 2.

This book seeks to answer 4 questions:

What are the implications of the changing distribution of global power from West to East, and how is it being affected by the new reality of a politically awakened humanity? Why is America’s global appeal waning, how ominous are the symptoms of America’s domestic and international decline, and how did America waste the unique global opportunity offered by the peaceful end of the Cold War? What would be the likely geopolitical consequences if America did decline by 2025, and could China then assume America’s central role in world affairs? What ought to be a resurgent America’s major long-term geopolitical goals in order to shape a more vital and larger West and to engage cooperatively the emerging and dynamic new East? America, Zbigniew Brzezinski argues, must define and pursue a comprehensive and long-term geopolitical vision, a vision that is responsive to the challenges of the changing historical context. This book seeks to provide the strategic blueprint for that vision.

5. The Unfinished February 14 Uprising: What Next for Bahrain? Dirksen, 9:30-11 am February

|

Dirksen Senate Office Building, Room 106

|

|

|

POMED DC Events Calendar

|

|

|

alex.russell@pomed.org

|

|

|

As the February 14th anniversary of the start of mass protests in Bahrain approaches, now is a critical time to analyze events over the past few months and discuss expectations for the coming weeks. With the release of the BICI report in late November, which detailed systematic human rights abuses and a government crackdown against peaceful protesters, the Government of Bahrain was tasked with a long list of reforms and recommendations. At this juncture, nearly two months after the release of the report, it is essential for the United States to debate the Kingdom’s reforms and how to move Bahrain forward on a path of democratic progress. Human rights groups continue to raise significant human rights concerns with respect to the situation on the ground. What are some of these concerns? What are the current realities on the ground in Bahrain? What are the strategies of the country’s political opposition parties and revolutionary youth movement, and how is the monarchy reacting? What are some expectations and challenges regarding the palace-led reform process? And, importantly, what constructive roles can the U.S. play in encouraging meaningful reform at this time? Please join us for a discussion of these issues with: Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) Elliott Abrams Senior Fellow for Middle Eastern Studies, Council on Foreign Relations Joost Hiltermann Deputy Program Director, Middle East and North Africa, International Crisis Group Colin Kahl Associate Professor, Georgetown University; Senior Fellow, Center for a New American Security Moderator: Stephen McInerney Executive Director, Project on Middle East Democracy To RSVP: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/viewform?formkey=dGFWVEU3dzBVNUtiTzFKYW5OVlZ3UXc6MQ This event is sponsored by the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), the National Security Network, and the Foreign Policy Initiative. For more information, visit: http://pomed.org/the-unfinished-february-14-uprising-what-next-for-bahrain-2/

|

6. An Assessment of Iran’s Upcoming Parliamentary Elections, Woodrow Wilson Center, 12-1:15 pm February 9

with

Hosein Ghazian

and

Geneive Abdo

Location:

-

Geneive Abdo //Director, Iran Program, The Century Foundation

-

Visiting Scholar, Syracuse University

This event requires a ticket or RSVP

This event requires a ticket or RSVP

The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) and the Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding

invite you to

One Year Later:

Has the Arab Spring Lived Up to Expectations?

A public panel featuring:

John L. Esposito

University Professor & Founding Director

ACMCU, Georgetown University

Heba Raouf

Associate Professor

Cairo University

Radwan Ziadeh

Fellow, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding

Senior Fellow, United States Institute of Peace

Moderated by:

Farid Senzai

Director of Research

Institute for Social Policy and Understanding

February 9, 2012 – 4:00-6:00 pm

Georgetown University Hotel & Conference Center | Salon H

One year has passed since protestors took to the streets across the Arab World. Join the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding and the Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding for an engaging panel on what progress has been made on the ground and where the revolution will go from here.

_______________________

John L. Esposito is University Professor, Professor of Religion and International Affairs and of Islamic Studies and Founding Director of the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at the Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. Esposito specializes in Islam, political Islam from North Africa to Southeast Asia, and Religion and International Affairs. He is Editor-in-Chief of Oxford Islamic Studies Online and Series Editor: Oxford Library of Islamic Studies, Editor-in-Chief of the six-volume The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World, The Oxford History of Islam (a Book-of-the-Month Club selection), The Oxford Dictionary of Islam, The Islamic World: Past and Present, and Oxford Islamic Studies Online. His more than forty five books include Islamophobia and the Challenge of Pluralism in the 21st Century, The Future of Islam, Who Speaks for Islam? What a Billion Muslims Really Think (with Dalia Mogahed), Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam (a Washington Post and Boston Globe best seller), The Islamic Threat: Myth or Reality?, Islam and Politics, Political Islam: Radicalism, Revolution or Reform?, Islam and Democracy (with J. Voll). His writings have been translated into more than 35 languages, including Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Bahasa Indonesia, Urdu, European languages, Japanese and Chinese. A former President of the Middle East Studies Association of North America and of the American Council for the Study of Islamic Societies, Vice Chair of the Center for the Study of Islam and Democracy, and member of the World Economic Forum’s Council of 100 Leaders, he is currently Vice President (2012) and President Elect (2013) of the American Academy of Religion, a member of the E. C. European Network of Experts on De-Radicalisation and the board of C-1 World Dialogue and an ambassador for the UN Alliance of Civilizations. Esposito is recipient of the American Academy of Religion’s Martin E. Marty Award for the Public Understanding of Religion and of Pakistan’s Quaid-i-Azzam Award for Outstanding Contributions in Islamic Studies and the School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University Award for Outstanding Teaching.

Heba Raouf Ezzat holds a Ph.D in political theory and has been teaching at Cairo University since 1987, and is also an affiliate professor the American University in Cairo (since 2006). She currently serves as Visiting Senior Fellow at the Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding. Her research, publications and activism is focused on comparative political theory, women in Islam, global civil society, new social movements and sociology of the virtual space. She is also a cofounder of Islamonline.net which is now Onislam.net, an academic advisor of many youth civil initiatives, the member of the Board of Trustees of Alexandria Trust for Education – London, and the Head of the Board of Trustees of the Republican Consent Foundation – Cairo. She was a research fellow at the University of Westminster (UK) (1995-1996), the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies (1998 and 2012), and the Center for Middle East Studies, University of California-Berkeley (2010). She recently participated in establishing the House of Wisdom, the first independent Egyptian Think Tank founded after the Egyptian revolution 2011.

Radwan Ziadeh is a Fellow at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), a Senior Fellow at the United States Institute of Peace, and a Dubai Initiative associate at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He is the founder and director of the Damascus Center for Human Rights Studies in Syria and co-founder and executive director of the Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Washington, D.C.

Farid Senzai is Director of Research at ISPU and Assistant Professor of Political Science at Santa Clara University. Dr. Senzai was previously a research associate at the Brookings Institution, where he studied U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East, and a research analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations, where he worked on the Muslim Politics project. He served as a consultant for Oxford Analytica and the World Bank. Dr. Senzai is currently on the advisory board of The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life where he has contributed to several national and global surveys on Muslim attitudes. His recent co-authored book is Educating the Muslims of America (Oxford University Press, 2009). Dr. Senzai received a M.A. in international affairs from Columbia University and a Ph.D. in politics and international relations from Oxford University.

_______________________________

Please RSVP here: http://arabspringispu.eventbrite.com/

For a map and directions to the GU Conference Center, please visit: http://www.acc-guhotelandconferencecenter.com/map-directions/

mem297@georgetown.edu

-

Dr. John Hamre

President and CEO, CSISModerated by

Dr. Bulent Aliriza

Director and Senior Associate, CSIS Turkey ProjectCenter for Strategic and International Studies

B1 Conference Room

1800 K. St. NW, Washington, DC 20006

9. China, Pakistan and Afghanistan: Security and Trade, 12:30-2 pm, Rome Auditorium, SAIS

What threatens the United States?

The Council on Foreign Relations published its Preventive Priorities Survey for 2012 last week. What does it tell us about the threats the United States faces in this second decade of the 21st century?

Looking at the ten Tier 1 contingencies “that directly threaten the U.S. homeland, are likely to trigger U.S. military involvement because of treaty commitments, or threaten the supplies of critical U.S. strategic resources,” only three are defined as military threats:

- a major military incident with China involving U.S. or allied forces

- an Iranian nuclear crisis (e.g., surprise advances in nuclear weapons/delivery capability, Israeli response)

- a U.S.-Pakistan military confrontation, triggered by a terror attack or U.S. counterterror operations

Two others might also involve a military threat, though the first is more likely from a terrorist source:

- a mass casualty attack on the U.S. homeland or on a treaty ally

- a severe North Korean crisis (e.g., armed provocations, internal political instability, advances in nuclear weapons/ICBM capability)

The remaining five involve mainly non-military contingencies:

- a highly disruptive cyberattack on U.S. critical infrastructure (e.g., telecommunications, electrical power, gas and oil, water supply, banking and finance, transportation, and emergency services)

- a significant increase in drug trafficking violence in Mexico that spills over into the United States

- severe internal instability in Pakistan, triggered by a civil-military crisis or terror attacks

- political instability in Saudi Arabia that endangers global oil supplies

- intensification of the European sovereign debt crisis that leads to the collapse of the euro, triggering a double-dip U.S. recession and further limiting budgetary resources

Five of the Tier 2 contingencies “that affect countries of strategic importance to the United States but that do not involve a mutual-defense treaty commitment” are also at least partly military in character, though they don’t necessarily involve U.S. forces:

- a severe Indo-Pak crisis that carries risk of military escalation, triggered by major terror attack

- rising tension/naval incident in the eastern Mediterranean Sea between Turkey and Israel

- a major erosion of security and governance gains in Afghanistan with intensification of insurgency or terror attacks

- a South China Sea armed confrontation over competing territorial claims

- a mass casualty attack on Israel

But Tier 2 also involves predominantly non-military threats to U.S. interests, albeit with potential for military consequences:

- political instability in Egypt with wider regional implications

- an outbreak of widespread civil violence in Syria, with potential outside intervention

- an outbreak of widespread civil violence in Yemen

- rising sectarian tensions and renewed violence in Iraq

- growing instability in Bahrain that spurs further Saudi and/or Iranian military action

Likewise Tier 3 contingencies “that could have severe/widespread humanitarian consequences but in countries of limited strategic importance to the United States” include military threats to U.S. interests:

- military conflict between Sudan and South Sudan

- increased conflict in Somalia, with continued outside intervention

- renewed military conflict between Russia and Georgia

- an outbreak of military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, possibly over Nagorno Karabakh

And some non-military threats:

- heightened political instability and sectarian violence in Nigeria

- political instability in Venezuela surrounding the October 2012 elections or post-Chavez succession

- political instability in Kenya surrounding the August 2012 elections

- an intensification of political instability and violence in Libya

- violent election-related instability in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- political instability/resurgent ethnic violence in Kyrgyzstan

I don’t mean to suggest in any way that the military is irrelevant to these “non-military” threats. But it is not the only tool needed to meet these contingencies, or even to meet the military ones. And if you begin thinking about preventive action, which is what the CFR unit that publishes this material does, there are clearly major non-military dimensions to what is needed to meet even the threats that take primarily military form.

And for those who read this blog because it publishes sometimes on the Balkans, please note: the region are nowhere to be seen on this list of 30 priorities for the United States.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts