Tag: Turkey

The worst of all possible worlds

It is getting hard to keep score, though this graphic from Al Jazeera English may help. Today’s big news is the defection of Syria’s prime minister, who didn’t like Bashar al Asad’s “war crimes and genocide.” About time he noticed. There are reports also of more military defections, even as the battle for Aleppo continues.

Does any of this matter? Or does Bashar get to hold on to his shrinking turf despite going into hiding and losing the support of regime stalwarts?

Michael Hanna offers an important part of the answer in a Tweet this morning:

Syrian defections follow strictly sectarian pattern, likely hardening core support. 1st big Alawi defection, if it comes,will be devastating

The Asad regime is increasingly relying on a narrow base of Alawite/Shia (about 12-13% of the population) support, as Sunnis (like the prime minister) peel away and denounce Bashar’s violence against the civilian population, which is majority Sunni. Christians and Druze have also been distancing themselves, and Kurds have taken up arms against the regime (without however aligning themselves with the opposition). The opposition draws its strength from the majority population and is supported by Sunni powers like Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. What we are witnessing is a regional sectarian war in the making, one that could last a long time and involve ever-widening circles in the Levant.

The Alawites fight tenaciously because they think they know what is coming. This is an “existential” war for them: if the lose, they believe they will be wiped out.

That, along with Russian and Iranian support, could make this go on for a long time. If it does, the consequences for Syria and the region will be devastating. Damascus has already unleashed extremist Syrian Kurds to attack inside Turkey. Jordan is absorbing more than 100,000 Syrian refugees. Iraq’s efforts to guard its border with Syria have led to a confrontation with its own Kurdish peshmerga. Fighting between Sunnis and Alawites has spread to Lebanon, which is also absorbing large numbers of Syrian refugees. The Syrian opposition claims to have captured 48 Iranians in Damascus, sent there to help the regime (Tehran unabashedly claims they were religious pilgrims).

Breaking this self-reinforcing cycle of sectarian polarization is an interest broadly shared in the international community. As The Economist pointed out last week, Russian interests won’t be served if Syria descends into total chaos. Some would like to suggest that territorial separation is a solution. This is nonsense: no one will agree on the lines to be drawn, which will be decided by force of arms directed against the civilian population. That is the truth of what happened in Bosnia, however much the myth-makers delude themselves.

There are several ways the violence might end:

- a definitive victory by the opposition (it is hard now to picture a definitive victory by the regime).

- an international intervention to separate the warring forces and impose what the U.S. military likes to call a “safe and secure environment.”

- a coup from within the regime, followed by a “pacted” (negotiated) transition.

Any of these would be better than continuation of the current chaos, which is the worst of all possible worlds. But I’m afraid that is the mostly likely course of events until Moscow and Washington get together and decide to collaborate in ending the bloodshed.

Iraq and its Arab neighbors: no port in the storm

Speakers painted a bleak picture of a lebanized Iraq, weakened by internal divisions and unable to craft coherent regional policies, at a Middle East Institute event today.

Ambassador Samir Sumaida’ie, former Iraqi ambassador to the United States, likened contemporary Iraq to a leaking ship, barely floating on the regional political waters as storms rage all around. The Ambassador bemoaned the lack of support for secularists after the American invasion and lambasted American support to Iraqi Sunni and Shi’a Islamists. This policy worsened sectarianism. The United States left Iraq with a constitution that forbids discrimination on the basis of religion, but with an unwritten political pact that “lebanizes” the executive branch, with the presidency Kurdish, the prime ministry Shi’a and the speaker of parliament Sunni. This built-in sectarianism weakens the Iraqi state.

These internal divisions are at the heart of Iraq’s tepid relations with its Arab neighbors, who are standoffish, especially towards the Shi’a and Kurds. The Kurdistan Regional government conducts its own foreign policy, including a representative in Washington. The Ambassador is pessimistic about Iraq’s immediate future in the region: “it is in a crisis, but the horizon seems to be more of the same.” Only if Iraq improves its internal cohesion and mends fences with Kuwait and Turkey can it avoid being engulfed by the ongoing political firestorms raging in Syria.

Kenneth Pollack, Senior Fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institute, focused on the “brightly burning” Syrian flame. Like Ambassador Sumaida’ie, he bemoans Iraq’s internal lebanization, especially with regard to policies towards Syria. There is no coherent Iraqi policy, but rather multiple Iraqi policies toward Syria. The complex interplay of internal factionalization within Iraq’s weak state muddles its external relations, as each faction approaches the region in general, and Syria in particular, with an eye towards its own interests. The Kurds see events in Syria as an opportunity, not a threat; Masoud Barzani is strengthening ties to Turkey, trying to reassure the Turks that Kurdish interests are aligned with their own in the case of Syria. Sunni tribal leaders also see Syria as more of an opportunity than a threat: Syrian Sunnis in their view are throwing off the yoke of an Iranian-backed Shi’a minority. If it can happen in Syria, the thinking goes, why not in Baghdad? Despite some sympathy for the Syrian opposition, Iraqi Shi’a associated with Moqtada al Sadr are still wary of developments there, which threaten a regime aligned with Tehran. Prime Minister Maliki fears spillover from Syria that may damage Iraqi stability and security. This multiplicity of Iraqi approaches to Syria is driven by internal Iraqi political divisions, and is emblematic of the larger foreign and domestic policy problems facing Iraq.

Gregory Gause, professor of political science at the University of Vermont characterized Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy toward Iraq as passive. The Saudi view of Iraq and the Maliki government is negative, because they view the prime minister as an agent of Iran. The Saudis have done little or no outreach to Kurds or Iraqi Shi’a, and even with the Sunnis they have made no real appeal to Arabism. Saudi policy toward Iraq is a policy of complaint, not outreach. Saudi elites are focused on what appears to them a losing struggle for influence in the Middle East against Iran. This struggle for influence in the region plays out not through armies, but through contests for influence in the domestic politics of weak Arab states. The Saudis find Sunni allies, and Iran finds Shi’a allies. This sectarian alignment is counterproductive for the Saudis, because it gives Arab Shi’a in the region no choice but to ally with Iran. Ultimately, this will cause long-term problems for Saudi Arabia, Iraq and America, as it creates an atmosphere where al Qaeda type ideas can flourish. Other GCC states have largely followed Saudi Arabia’s lead.

John Desrocher, Director of the Office or Iraq Affairs at the Department of State focused on the positive, in terms of Iraq’s relations to its regional neighbors: Iraq and Kuwait have made “considerable progress in terms of resolving disputes,” relations with Jordan have improved, Saudi Arabia named an ambassador to Iraq for the first time since 1990, and Qatar airways now flies to Iraq. However, internal political divisions in Iraq have led to “real political gridlock” both in terms of domestic policy and regional relations.

Putin was right

Russia’s President said earlier this week:

It is better to involve Iran in the settlement (of the Syrian crisis)…The more Syria’s neighbors are involved in the settlement process the better. Ignoring these possibilities, these interests would be counterproductive, as diplomats say. It is better to secure its support. In any case it would complicate the process (if Iran is ignored).

Putin is right. UN/Arab League Special Envoy Kofi Annan is too: he also wanted Iran at Saturday’s meeting in Geneva, which is scheduled to include the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Turkey as well as Arab Leaguers Iraq, Kuwait and Qatar.

The Americans have been blocking Iran from attending, on grounds that Tehran is providing support–including lethal assistance–to the Assad regime. That is true. It is also the reason they should be there. So long as they meet the Americans’ red line–that attendees should accept that the purpose of the meeting is to begin a transition away from the Assad regime–it is far better to have them peeing from inside the tent out than from outside the tent in. No negotiated transition away from the Assad regime is going to get far if the Iranians are dead set against it.

If they agree to attend, it will cause serious problems inside Tehran with the Quds Force, the part of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard responsible for helping Bashar al Assad conduct the war he declared yesterday on his own people. Discomforting the Iranians should be welcome in Washington. If Iran had refused the invitation, which was likely, it would have been far easier to drive a wedge between them and the Russians, who are at least saying that they are not trying to protect Bashar al Assad’s hold on power.

Of course if they were to attend the Iranians would have raised issues that make Washington and some of its Arab friends uncomfortable. Most obvious is Saudi and Qatari arms shipments to the Syrian rebel forces, who this week attacked a television station, killing at least some civilians. But that issue will be raised in any event by the Russians, whether the Iranians are there or not.

The Iranians would likely also raise Bahrain, where a Sunni royal monarch rules over a largely Shia population. The repression there has been far less violent and abusive than what Alawite Bashar al Assad is doing in Sunni-majority Syria, but the Iranians will argue that if transition to majority rule is good for the one it is also good for the other. Does it have to get bloodier before the international community takes up the cause of the Bahraini Shia? This argument will get some sympathetic noises from Iraq, which is majority Shia, but not from Sunni Qatar, UAE or Kuwait.

Turkey, meanwhile, has downplayed the Syrian attacks on its fighter jets, which I am assured by a Turkish diplomat were in fact on reconnaissance, not training missions, as Ankara publicly claimed. The reconnaissance flights routinely cross momentarily into Syrian airspace because it is impossible to fly strictly along the irregular border between the two countries. Damascus shot down one, probably as a warning to its own pilots not to try to abscond, as one did last week. Israeli jets also routinely violate Syrian airspace, but it is a long time since Syria took a shot at one of them.

The Turks seem to have gotten what little moral support they wanted out of consultations on the Syrian attacks at NATO earlier this week. Ankara has decided to low key the affair, thus avoiding further frictions with Syria, which can respond to any Turkish moves by allowing Kurdish guerrillas to step up their cross-border attacks into Turkey.

This is a complicated part of the world, where there are wheels within wheels. Much as I dislike saying it, Putin was right to try to get all the main players in the room, lest some of those wheels continue to spin out of control if their masters haven’t been involved in the decisionmaking. But that isn’t likely to change anyone’s mind in Washington, where electoral pressures preclude inviting Iran to a meeting on Syria. Let’s hope that the meeting is nevertheless successful and that the plan it produces can be sold after the fact to Tehran, which otherwise may prove a spoiler.

Schizophrenic Turkey

The closing panel yesterday at the Middle East Institute’s Third Annual Conference on Turkey, on “Turkey’s Leadership Role in an Uncertain Middle East,” found plenty of uncertainty in Turkey’s role as well. Al-Jazeera Washington bureau chief Abderrahim Foukara opened the discussion with a look at the “schizophrenic” face of Turkey’s ascendancy in the Middle East. While many Arabs look to Turkey as a leader as well as a model of successful moderate political Islam, others see its rising profile in the region as a threat. This tension in Turkey’s regional role is evident in its relationships with Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Israel.

International Crisis Group’s Joost Hiltermann covered Turkey’s relations with Iraq, which appeared to be the most schizophrenic case. Turkey’s worsening relations with Baghdad and ever-growing partnership with Irbil are contributing to the centrifugal forces tearing Iraq apart, counter to Turkey’s stated objectives. Hiltermann’s recent trip to Ankara left him still confused about what Turkey hopes to achieve in Iraq, but he sees the current dynamic as negative.

Turkey wants a stable and unified Iraq as a way to provide regional stability, regional economic integration, a buffer against Iran, access to Iraqi oil and gas, and tempering of Kurdish nationalism in Turkey. On the last point, Ankara hopes to harness the Kurdish Regional Government as a counterweight to the PKK, but its other main interests depend upon Iraqi unity and amicable ties with Baghdad. The current strain in relations stems from tension with Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and the Syrian crisis. Turkey’s overt opposition to al-Maliki’s party in the 2010 elections backfired when he won the day. Ankara-Baghdad relations have broken down further with suspicion in Iraq that a Sunni (Turkey-Gulf) alliance is gunning for the Syrian regime and will come after the regime in Baghdad next. The best way forward would be a rapprochement between Ankara and Baghdad, particularly an exchange of envoys, in order to prevent mutual suspicions from becoming self-fulfilling prophecies.

Freelance journalist Yigal Shleifer had the simplest diagnosis: Turkish-Israeli relations are anywhere from “dead and frozen” to “completely dead and deeply frozen.” The Gaza flotilla incident was simply the nail of the coffin, and since then the two sides have painted themselves into a corner. Turkey wants nothing less than a full apology, restitution, and the lifting of the blockade, while Israel is only willing to apologize for operational mistakes and cover some damages. In dealing with the crisis Israel was looking to “make up after the breakup,” while Turkey was negotiating “the terms of an amicable divorce.” Indicators for the near future are discouraging, particularly as both publics have become deeply skeptical of the other. Strategic partnership with Israel simply does not fit into Turkey’s evolving sense of purpose in the region, one piece of which is to be more outspoken in support of the Palestinian cause.

The lack of high-level communication is a recipe for disaster; the flotilla incident would likely not have gone so sour if relations had not already been strained to the point of stymying communication. Shleifer’s recommendation is a concerted diplomatic push, which will have to be American. Restoring relations to a level of trust is imperative for both. For Israel, it’s a question of security, but for Turkey it’s necessary for the development of its role as regional mediator as well as political, economic, and religious crossroads.

Robin Wright of the Woodrow Wilson Center characterized Syria and Iran as representing some of the profoundest achievements and toughest challenges of Turkish politics in the last few years. The AKP has been fond of talking about 360-degree strategic depth, but Iran and Syria have called this approach into question. Iran has become an important energy source and trading partner for Turkey under the AKP. It has also provided an opportunity for Turkey to flex its diplomatic muscle, as the biggest player in nuclear negotiations outside the P5+1. But Iran’s recalcitrance has proven increasingly frustrating for Turkey, and Turkey may find itself having to choose between closer relations with Iran or with the emerging bloc led by Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Syria is an even starker challenge. Erdogan and Asad used to call each other personal friends, and the countries even engaged in joint military exercises. The rebellion has flipped the situation, with Turkey becoming the base for the opposition Syrian National Council and Erdogan calling Asad’s tactics savage and his regime a clear and imminent threat. Wright does not see the possibility of normalized relations anytime soon, especially under the current leaders.

The conflicts over Iran and Syria have pushed Turkey ever more toward the West, undermining its 360-degree diplomacy. What Turkey does in the next year in terms of its alliances in the East and the West will do a lot to determine the direction of its development as a regional and international player.

The overall impression was one of Turkey at a historical crossroads paralleling its traditional role as geographic and cultural crossroads. Turkey now has issues with most of its neighbors, yet its potential for political and economic growth is huge. It has successfully cast itself as the indispensible mediator. The political role it envisions is both regional strongman and regional middleman. It will also play an important role in helping the Arab world define a new order in the wake of the Arab Spring, as a model and as a political partner.

Turkey has been steadily strengthening its economic ties with its European and Middle Eastern neighbors, but the political realm will require more tradeoffs: between Europe and Asia, Iran and the Sunni powers of the Gulf, Israel and Arab states. Yigal Shleifer’s recollection of a Turkish airline ad touting Istanbul as a connection to both Tel Aviv and Tehran was illustrative.

The consensus on the panel was that even with these ambiguities of strategic direction, Turkey has carved an independent place for itself on the regional and international scene. Turkey’s clout will almost certainly increase with the rise of moderate Islamist governments in Arab Spring countries, but to navigate the new environment it will have to make tough choices about its alliances and its guiding foreign policy principles.

A lot depends on your priorities

I did a quick writeup of Senator McCain’s appearance yesterday at the Middle East Institute Turkey Conference, which is posted on their website this morning (thank a spam filter for the delay):

Senator John McCain was uncharacteristically subdued in a key note address yesterday to the Middle East Institute/Institute of Turkish Studies conference on Turkey. He prodded President Obama to be more outspoken in denouncing the Assad regime and advocated a “safe zone” inside Syria along the Turkish border, but only in response to a question. He discounted the likelihood of NATO action, which the Europeans oppose, and suggested that the U.S. and Turkey should form the core of a coalition of the willing to support the Syrian opposition with arms and training.

The Senator opened with a denunciation of the Syrian downing of a Turkish jet, calling it an unnecessary and unacceptable act of aggression. But then he turned quickly to focus on Turkey’s positive evolution into a more inclusive and representative democracy experiencing strong economic growth. He also noted troubling developments: Turkey’s jailing of journalists, its prosecutions of army officers and the deterioration of its relations with Israel.

The U.S., McCain said, should give wholehearted military and intelligence support to Turkey in its fight against Kurdish terrorists (the PKK). But the bilateral relationship should broaden its focus to free trade, military modernization, missile defense and strategic cooperation in Afghanistan, the Arab Spring and other contexts where democracy, human rights and rule of law are at stake. Turkey, he said, sets a standard for democracy in Muslim countries and is an attractive example to many throughout the Muslim world.

McCain appealed for stronger U.S. leadership in speaking up for the people of Syria and countering Russian and Iranian support to the Assad regime, which includes both arms and personnel. A “safe zone” on the Turkish/Syrian border would provide the fragmented and unreliable opposition with a place where it could coalesce. This would require intervention from the air (as in Bosnia and Kosovo) but not, he thought, boots on the ground (forgetting of course that on the “day after” U.S. troops were needed in both Bosnia and Kosovo). Asked about the Annan peace plan that provides for a peaceful transition, McCain reacted with disdain, saying that Bashar al Assad would have to be forced out.

The current situation, McCain emphasized, is not acceptable. Sectarian violence is on the increase, as is exploitation of the situation by extremists. It will only get worse if the U.S. fails to lead. It is not even leading from behind at this point. It is not enough for the White House to say that Bashar al Assad’s fall is inevitable. We have to make it happen.

McCain acknowledged American war weariness but underlined the moral imperative to speak out and to act. Absent from his remarks was consideration of the impact of American and Turkish air attacks to create a “safe zone” on Russian support for the P5+1 negotiations with Iranian on its nuclear program and on the Northern Distribution Network that supplies NATO troops in Afghanistan. Those who think Afghanistan and Iran should have priority in American foreign policy won’t go along with the Senator, almost no matter what Bashar al Assad does to his own people. A lot of what people think should be done in Syria depends on what your priorities are.

Reconciliation: a new vision for OSCE?

I am speaking at the OSCE “Security Days” today in Vienna on a panel devoted to this topic. Here is what I plan to say, more or less:

Reconciliation is hard. Do I want to be reconciled to someone who has done me harm? I may want an apology, compensation, an eye for an eye, but why would I want to be reconciled to something I regard as wrong, harmful, and even evil?

At the personal level, I may be able to escape the need for reconciliation. I can harbor continuing resentment, emigrate, join a veterans’ organization and continue to dislike my enemy. I can hope that my enemy is prosecuted for his crimes and is sent away for a long time. I don’t really have to accept his behavior. Many don’t.

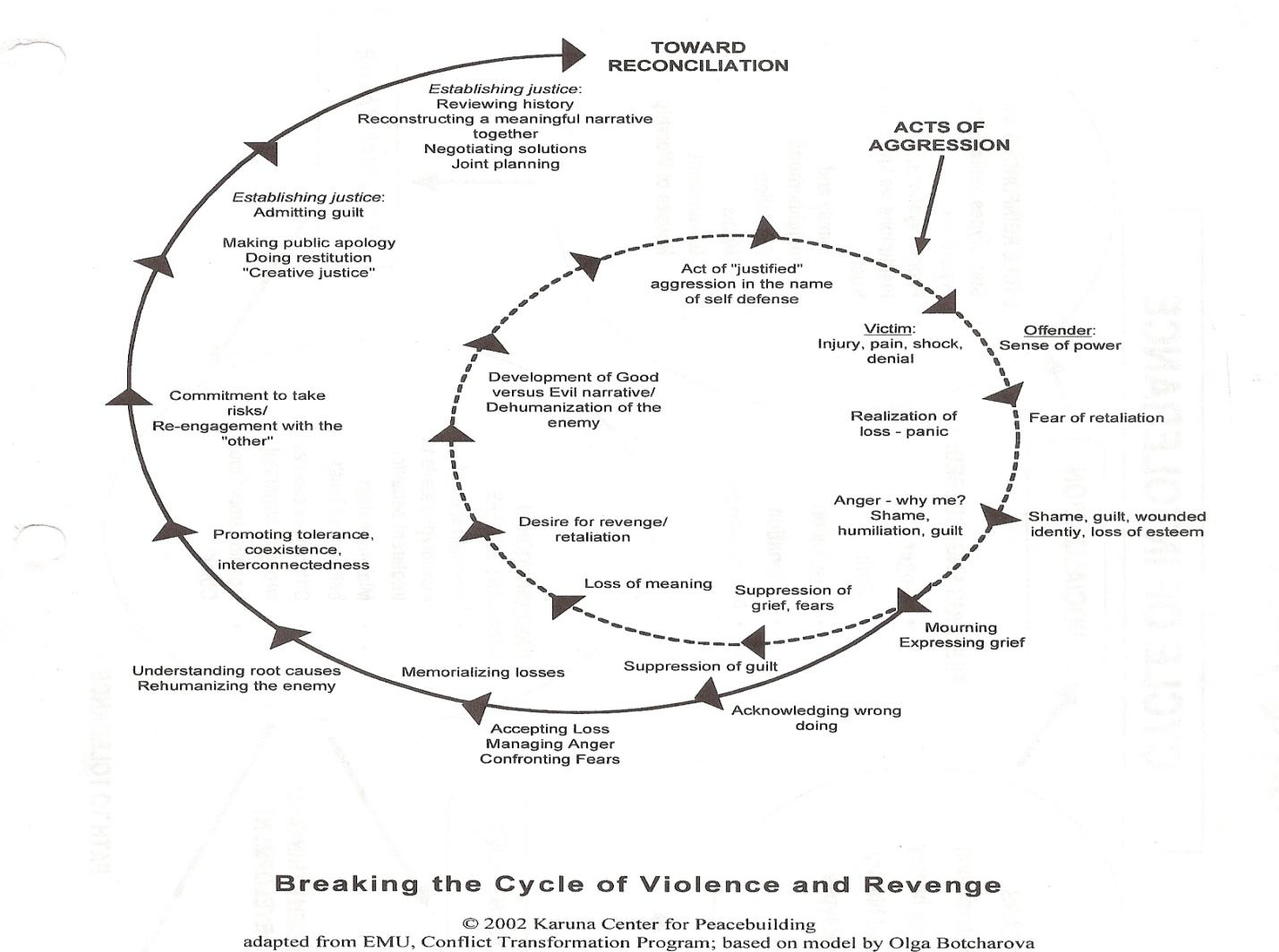

But at the societal level lack of reconciliation has consequences. It is a formula for more violence. We remain trapped in the inner circle of this classic diagram, in a cycle of violence. Victims, feeling loss and desire for revenge, end up attacking those they believe to be perpetrators, who eventually react with violence:

What takes us out of the cycle of violence and retaliation? The critical step is acknowledging wrong doing, a step full of risk for perpetrators and meaning for victims. But once wrong doing is acknowledged, victims can begin to accept loss, manage anger and confront fears. This initiates a virtuous cycle of mutual understanding, re-engagement, admission of guilt, steps toward justice and writing a common history.

What has all this got to do with OSCE? Some OSCE countries are still stuck in the inner cycle of violence, despite dialogue focused on practical confidence-building measures that moves the parties closer. But the vital step of acknowledging wrong has either been skipped entirely or given short shrift. Conflict management is a core OSCE function. The job will not be complete until OSCE re-discovers its role in reconciliation.

I know the Balkans best. We aren’t past the step of acknowledging wrongdoing in Bosnia and Kosovo. Even Greece and Macedonia are trapped in a cycle that could become violent. The situation is less than fully reconciled in Turkey, the Caucasus, Moldova and I imagine other places I know less well. Is there a good example of Balkans reconciliation? The best I know is Montenegro’s apology to Croatia for shelling Dubrovnik. That allowed them to build the positive relationship they have today.

Should reconciliation be a new OSCE vision? Its leadership and member states will decide, but here are questions I would ask if I were considering the proposition:

- How pervasive is the need for reconciliation in the OSCE?

- Would it make a real difference if reconciliation could be established as a norm?

- If it did become a new norm, how would we know when it is achieved?

- What would we do differently from what we do today?

I was in Kosovo earlier this month. There is little sign there of reconciliation: it is difficult for Belgrade and Pristina to talk with each other, they have reached agreements under pressure that are largely unimplemented, OSCE and other international organizations maintain operations there because of the risk of violence. There is little acknowledgement of wrong doing. The memorials are all one-sided: I drove past many well-marked KLA graveyards. We have definitely not reached the outer circle yet.

Would it make a difference if there were acknowledgement of wrong doing? Yes, it would. It would have to be mutual, since a good deal of harm has been done on both sides, even if the magnitude of the harm differs. Self-sustaining security in Kosovo will not be possible until that step has been taken. I would say the same thing about Bosnia, Kyrgystan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Turkey and Armenia. Your North African partners might benefit from focus on reconciliation.

Dialogue is good. Reconciliation is better. Maybe OSCE should take the next difficult but logical step.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts